Most of the complaints and approaches we received about Australian Government agencies in our jurisdiction related to the following four agencies:

- The Department of Human Services (Centrelink, Medicare and Child Support)

- Australia Post

- The Department of Immigration and Border Protection

- The Australian Taxation Office.

This section discusses our work with those four agencies, as well as the specialist roles we perform, including the:

- Defence Force Ombudsman

- Overseas Students Ombudsman

- Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- inspection functions

- Public Interest Disclosure scheme

- international program.

Social Services portfolio

While most complaints to our office are about the actions and decisions of a single Government agency, many of the underlying systemic issues are in fact the responsibility of more than one agency.

In the Social Services portfolio, there are several key agencies that variously deliver, or set policy for the administration and delivery of, payments and services to the Australian community. In some instances an agency will perform both a policy and delivery role.

A number of Social Service agencies are discussed in detail in this section:

- the Department of Human Services, which delivers the Australian Government’s Centrelink, Child Support and Medicare programs

- the Department of Employment, which has policy responsibility for the delivery of job services programs to people who are required to look for work in order to receive income support payments, as well as those who elect to access job services on a voluntary basis

- the Department of Social Services, which has policy responsibility for (among other things) social security and family assistance payments, child support, housing, child care and disability. It also directly administers a small number of programs directly to the public

- the National Disability Insurance Agency, which has responsibility for administering the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

Department of Human Services

In 2014-15 we received 8116 complaints about DHS programs. This represents a 21.5% increase against the 6682 complaints we received in 2013-14, largely as a result of the 26.5% increase in the number of Centrelink complaints.

Complaints about the Centrelink program made up 77.4% of complaints about DHS, followed by 18.1% about the Child Support program. Of the remaining complaints, most were about Medicare and the early release of superannuation benefits programs.

DHS - Centrelink

Centrelink delivers social security and family assistance payments, plus a range of other payments and services to people in the Australian community, and some people overseas.

Complaints about Centrelink (and its predecessors) have always represented a substantial proportion of the complaints to this office. Although we receive more complaints about Centrelink than any other Commonwealth program or agency, we recognise that this is largely tied to the size and complexity of its service-delivery responsibilities.

In 2013-14 DHS paid out $159.2 billion to customers in respect of programs across the Australian Government and touched the lives of around 99 per cent of Australians' through the delivery of payments and services.1 It is inevitable that errors and delays will occur in an operation of this scale. However, the potential for these errors to impact on the lives of a significant number of Australians means it is important to minimise these mistakes and their effect as much as possible.

Statistics

In 2014-15 we received 6280 complaints about Centrelink, an increase of 26.5% on the 4966 we received in 2013-14. This increase follows two years of reduced complaints about Centrelink. While it reflects a greater number of complaints across the board, there has been a particular increase in complaints about difficulties accessing DHS services and its own phone and online complaints mechanisms. These issues are discussed in greater detail below under Implementation of recommendations in Centrelink Service Delivery report.

During 2014-15 we investigated 8.7% of all finalised Centrelink complaints compared to the 10.7% we investigated during 2013-14.

This reduction is largely explained by two factors; namely, an increase in the number of referrals to the DHS Feedback and Complaints service where a complainant has not already accessed it, and warm transfers' to DHS's internal complaint service for resolution where a complainant is vulnerable or requires assistance to communicate their complaint.

This warm transfer' process allows DHS the opportunity to resolve the complainant's concerns in the first instance without the need for investigation by our office. At the time of transfer the complainant is invited to contact the Ombudsman again if they are dissatisfied or do not hear from Centrelink within the agreed timeframe.

Significant issues

Implementation of recommendations in Centrelink Service Delivery report

In April 2014 we published an own motion report concerning service delivery complaints about the Centrelink program. There were 33 sub-recommendations made about 12 areas of Centrelink's administrative practices, ranging from call wait times on its phone lines to the accessibility of its internal complaint-handling processes.

In March 2015 we commenced an own motion investigation to assess the work DHS had done to implement those recommendations. We published a further report detailing the status of the recommendations in September 2015. Details of that report will be discussed in next year's annual report.

We will continue to engage with DHS into 2015-16 as it works to further improve its service delivery and overcome the remaining service barriers and challenges affecting its customers.

Implementation of changes to residential aged care fee assessments

From 1 July 2014, as part of ongoing reforms to the aged care system, the arrangements for calculating residential aged care fees changed, with DHS taking over responsibility from DSS for assessing those fees.

In late 2014 we received a cluster of complaints about delays in processing of fee assessment applications. People also complained about fee assessments that were affected by errors and instances where people were sent multiple but contradictory assessment letters. The impacts of these issues varied.

Some people were advised by the aged care facility that they were unable to secure a permanent place until they had received notification of an aged care assessment determination, while some were charged higher respite care fees until they received their assessment. Others paid a much higher fee to the provider than they were ultimately assessed to pay in their corrected assessment.

Many complainants raised concerns that the higher fees depleted their funds, forcing some to make hard decisions about as whether their loved one could remain in the aged care facility. They also complained about out-of-pocket expenses incurred from juggling finances while trying to meet the higher fees, pending receipt of a corrected assessment notification and subsequent reconciliation process with the aged care facility.

Overpaid fees meant people needed to negotiate a refund with the provider, sometimes encountering resistance because providers were not prepared to review their fees until they had received advice from DHS of the possible refund amount.

Our investigations, and information provided at DHS briefings, highlighted issues with the quality and timeliness of the fee assessments and with the transfer of data relevant to the assessment. Both DHS and DVA have been affected by system issues.

DHS became aware of the issues shortly after implementation and applied a manual quality-checking process for every automated assessment letter it produced, replacing incorrect letters with manual letters.

At the time a lack of established communication protocols between DHS and DVA also added to the delay in resolving complaints and led to customers' frustration as they bounced' between departments. Multiple aged care phone lines maintained by all three departments (DHS, DVA and DSS) further complicated complaint resolution.

Our office met with DHS several times, and with DVA, to discuss the complaint issues. Those discussions centred on the errors made, the fixes they had applied and the strategies DHS and DVA had put in place to rectify the communication barriers and establish interdepartmental complaint-handling processes.

We have continued to receive complaints that seem to be about difficulties in the transfer of data from DVA to DHS and vice versa, but note that these appear to relate to issues that existed prior to the system fixes that were implemented by DHS up to and including March 2015. We have written to the departments about the issues identified in the complaints to this office.

We intend to remain in discussions with DHS and DVA to ensure that both departments have resolved the issues with data transfer and resultant assessments. We have encouraged both departments to actively consider whether any of its customers were financially disadvantaged by an incorrect assessment or a delay in issuing an assessment.

We suggested that the departments invite any customers in that position to make a claim under the Compensation for the Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) scheme. DHS has agreed to include information about the CDDA scheme in its letters to affected customers. We also suggested that a comprehensive review into the multiple causes of the problems be undertaken so as to ensure they do not occur again in respect of this program or others.

DHS has confirmed review processes were undertaken and that this information will be used to feed into future changes. It has also committed to continue to engage with this office to support future change processes.

CASE STUDY

Mrs A complained there had been several errors in the calculation of the aged care fee for her mother, Mrs B. Mrs B received a DVA payment and entered permanent care in June 2014. DVA transmitted Mrs B's income and asset information to DHS in August 2014. However, Mrs B's record had been duplicated in DHS's system and DVA's data was attached to the wrong record. DHS's system wrongly determined that Mrs B's details had not been received and assessed her as liable to pay a high level of fees.

Mrs A contacted DHS three times in late 2014 and each time she was informed she would need to speak to DVA. In January 2015 DHS identified the DVA data had been attached to the wrong record and recalculated Mrs B's fees. DHS determined that she was entitled to a refund from the provider of almost $17,000 for overpaid fees. DHS attempted to permanently correct the error, but in April 2015 it realised it had not received further data from DVA. In May 2015 DHS corrected Mrs B's record again and determined she was owed a further $6,700 in overpaid fees.

After being contacted by our office DHS examined Mrs B's record once more, DHS contacted DVA to confirm the correct record identification number was noted on the DVA record. At this time it identified that DVA still had the duplicate record on its system. DVA corrected the error, following which DHS contacted Mrs A to explain the events and apologise. DHS also wrote to the provider to explain the refunds that were owed to Mrs B. Our office informed Mrs A about the CDDA scheme.

Interaction between child support and Family Tax Benefit

Over the past year we have received many complaints from people who have incurred Family Tax Benefit (FTB) debts as a result of retrospective changes to their child support assessment. We consider that these complaints highlight the importance of the Centrelink and Child Support programs ensuring their respective letters alert FTB recipients to the potential for FTB debts if they elect to collect their child support entitlement directly from the paying parent, rather than having DHS collect the amount for them. We continue to discuss these issues with DHS and the policy department, the Department of Social Services.

Restricted servicing arrangements for certain DHS customers

Our last two Annual Reports mentioned the arrangements DHS has available to impose service restrictions on some customers to manage the way they interact with DHS. We are satisfied that in many cases this is a sensible practice, which aims to protect staff and other customers from risks presented by physical or verbal abuse.

However, we continue to receive complaints, albeit at a reduced rate, from DHS customers who are unhappy that their access to DHS services has been limited. Our investigations of these matters indicate that DHS generally manages these cases well.

However, we consider that some areas of DHS's administration of these arrangements could be improved. For example, recent complaints indicate that staff do not always clearly communicate the reasons and terms of the restrictions to customers, or record these in detail on DHS's records.

Major activities

In addition to the remedies we have obtained for individuals via investigation of their complaints, our major outcomes related to the Centrelink program include:

- the ongoing application of our warm transfer' arrangements to refer certain complaints to DHS's internal complaint service for prompt resolution

- roundtable meetings with community groups in Perth and Melbourne to discuss their experience of Centrelink's service delivery

CASE STUDY

Mr B complained to our office on behalf of his wife, Mrs B, about DHS's decision to issue her with a letter of warning for inappropriate behaviour that took place when she attended a customer service centre. Mrs B disagreed that she had behaved unreasonably and was unhappy that DHS had warned her she may be subject to a restricted servicing arrangement if that behaviour occurred in the future.

Our investigation concluded that, although we could not be critical of DHS's decision to issue a warning to Mrs B, we were concerned by the lack of detail that was recorded on DHS's file regarding the incident and in the letter to Mrs B. We considered this lack of detail made it difficult for Mrs B or for DHS staff in the future to understand which aspects of Mrs B's behaviour were considered unreasonable, with a view to addressing that behaviour in subsequent interactions. We suggested improvements be made to the arrangements for recording, and communicating with customers about, instances of alleged inappropriate behaviour.

DHS has advised our office that it is currently conducting a review of its customer management strategies across all programs, and will incorporate our feedback into that review. We look forward to providing feedback to that review during 2015-16.

- the continuation of effective liaison arrangements with DHS to investigate Centrelink complaints and broader issues of interest

- regular engagement with DHS staff to discuss and resolve systemic issues in Centrelink complaints, through scheduled quarterly meetings and ad hoc meetings by telephone and in person.

DHS - Child Support

DHS's Child Support program assesses and, in some cases, transfers child support payments between separated parents and/or other carers of eligible children. DHS also registers and collects court-ordered spousal and child maintenance payments, and some overseas maintenance liabilities.

The Ombudsman has jurisdiction to investigate complaints about DHS's administration of a child support case.

Statistics

In 2014-15 we received 1468 complaints about Child Support, only a slight increase on 2013-14 when we received 1426.

We classify the issues in the complaints we receive about Child Support according to whether the complaint was made by a payee (the person entitled to receive child support) or the payer (the person assessed to pay child support). As in previous years, we received just over twice as many complaints from payers (67.2% of all Child Support complaints) as from payees (30.7%).

Reduction in number of investigations

During 2014-15 the proportion of complaints we investigated about Child Support dropped to 16.6%, compared to 18.4% in 2013-14. This continues the downward trend seen in past years resulting from our focus on encouraging complainants to allow DHS the opportunity to resolve their concerns in the first instance, either via complaints directly to DHS or via having their complaint warm transferred to DHS for priority response.

Significant issues

Use of amended taxable incomes arising from circumstances beyond the customer's control

We have received a number of complaints in 2014-15 from payers who complain that DHS cannot adjust their child support assessment to use an amended (reduced) income tax assessment. These complainants advise that the amended tax assessment was brought about by an error, omission or wrongdoing on the part of another person or organisation, and they believe it is unfair they should be assessed to pay a higher rate of child support as a result of circumstances beyond their control.

In response to our inquiries in these cases, DHS advised that it had sought policy guidance from the Department of Social Services (DSS). The advice from DSS was that it considered the Child Support (Assessment) Act 1989 allows DHS to use amended taxable incomes for child support assessments only in very limited instances, usually where there has been a conviction for fraud or tax evasion.

The complaints our office has considered demonstrate the potential for anomalous outcomes, whereby payers have had to pay substantially higher amounts of child support and/or lodge a time-consuming and intrusive application for a change of assessment in special circumstances (COA) in order to remedy a simple error.

Although we have seen DHS expedite the processing of the COA application in some instances, there is no guarantee of a favourable outcome and some payers have been required to continue to pay child support assessments that are not reflective of their actual earnings.

We are concerned that the current law and policy do not provide an effective or efficient way to address simple errors, particularly those beyond the paying parent's control. We are currently discussing this issue directly with DSS.

CASE STUDY

Mr C complained to our office that DHS had calculated his maintenance liability using a significantly inflated taxable income that resulted from an error made by the Australian Taxation Office. Although DHS accepted that the income used in Mr C's child support assessment was not representative of his actual income, it advised him that child support law did not allow it to administratively amend the assessment to reflect his true financial position.

DHS advised Mr C that he could seek to have his child support assessment amended via a change of assessment application, but he did not consider this was a suitable option as he did not wish to share his personal information with the other parent (the payee).

Areas of ongoing concern

In our 2013-14 Annual Report we noted three areas of complaints about Child Support where we intended to undertaken further analysis and engagement. These were:

- child support for children aged over 18

- complaints from payees where the paying parent had been able to avoid paying child support through relatively simple structuring of their finances

- FTB debts accrued by payees as a result of retrospective increases in their child support entitlement, where they have no reasonable prospect of receiving the unpaid additional child support.

We were pleased to find that, as a result of feedback from this office, DHS has taken action aimed at addressing the first two issues. However, we remain concerned about the issue of FTB debts and intend to continue to discuss this with DHS and DSS.

Looking forward

Child Support's updated case-management system

DHS's Cuba case-management system is in the process of being replaced. The first phase is scheduled for full implementation in the coming months. We have provided feedback to DHS over a number of years regarding the issues we have identified with the current system, and have also been involved in discussions regarding the improvements that are expected to be derived from the upgrades.

We are pleased that the upgrade is progressing and we understand that it will address a number of the issues we have raised with DHS in recent times. Last year's Annual Report referred to the issue of DHS's inability to collect overpayments from payees, as well as the need for payees and payers to receive clearer information about how the overpayment occurred and the options available to recover it.

A requirement of the new system is that it will be able to isolate an overpayment, identify the reason for it occurring and allow for DHS to make withholdings from income support payments.

Department of Employment

During 2014-15 our office saw a 53.1% increase in complaints about the Department of Employment with 344 complaints received this year compared to 224 in 2013-14. The majority of these complaints were recorded as being about the actions or decisions of job service providers.

Changes to jobseeker compliance framework

From 1 July 2014 the Government commenced a phased process for strengthening the jobseeker compliance framework'. This process implemented arrangements to place a greater onus on jobseekers to engage with employment service providers and to impose more stringent consequences where they failed to complete these engagements without a good reason.

As part of these reforms, employment service providers have been empowered to recommend to DHS that a jobseeker's income support payment be suspended where they have failed to attend an appointment without a good reason. While the provider makes only a recommendation, as long as the jobseeker is in fact receiving an income support payment and is required to participate in job services, the DHS ICT system will then automatically apply the suspension.

During the past six months we have seen a spike in complaints about employment service providers where a jobseeker has their payment suspended as a result of a failure to attend an appointment, and then experiences difficulty in identifying whether DHS or the provider is responsible for assisting them to reconnect.

We continue to liaise with the Department of Employment and DHS to highlight these situations, and to encourage them to identify ways to ensure customers are provided with clear information about the pathways for resolving non-attendance failures.

This collaboration will become increasingly important into the future as, from 1 July 2015, job services providers are also able to recommend that DHS impose a financial penalty (in the form of a reduced income support payment) where a jobseeker has failed to attend an appointment.

We understand that broad discretion will be available to providers in deciding whether it is appropriate to recommend a financial penalty in the jobseeker's particular circumstances. DHS staff will then consider the recommendation and make contact with the jobseeker before making a final decision.

DHS already applies financial penalties for failure to comply with mutual obligation requirements, including serious non-compliance, but these penalties may apply for even a first non-attendance failure. We will be monitoring complaints in this area closely into 2015-16 to understand the practical implications for jobseekers, and will also engage with the Department of Employment and DHS to discuss their respective approaches to the new compliance arrangements.

National Disability Insurance Agency

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) is the agency responsible for administering the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), a government scheme that funds supports for people with a permanent and significant disability that affects their ability to take part in everyday activities.

At present, the NDIS is being conducted on a trial basis in seven sites across Australia, with the national rollout to be completed between 1 July 2016 and 30 June 2019. All states and territories except Queensland are involved in the trial.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman has jurisdiction to investigate the administrative actions of the NDIA. We have received less than 40 complaints to date, most of which have centred on delays in scheduling a planning meeting, disagreements about what is included in the participant's support plan and dissatisfaction with their assigned planner.

Major activities

Engagement

Over the past year we have visited the ACT trial site and regularly engaged with the NDIA and a number of disability advocacy organisations to discuss emerging issues. Over 2015-16 we plan to visit a number of the other NDIA trial sites, with a view to understanding participants' experience of the NDIS and improving public awareness of the Ombudsman's role in considering complaints about the NDIA.

Submission to proposal for an NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Framework

In February 2015 DSS commenced consultations regarding a proposed NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Framework. The consultation sought views regarding how the Government could ensure the NDIS provides quality support, choice and control, and keeps participants safe from harm. It focused on:

- systems for handling of complaints

- NDIA provider framework

- vetting of provider staff

- protections for self-managing participants

- reducing and eliminating the use of restrictive practices.

The Ombudsman made a submission regarding the framework, which was prepared following consultation with state and territory Ombudsmen. We made particular recommendations regarding the key principles that should underpin a strong complaint and oversight function, most notably that the oversight body should be independent, well-resourced and have authority to handle complaints in a tailored, person-centric manner.

The submission asserted that, in light of these key principles and his office's experience, geographic coverage, presence, networks, business processes and infrastructure, the Commonwealth Ombudsman is well placed to provide the NDIS oversight and complaint function. We await the Government's consideration of our proposal.

Department of Social Services

The Department of Social Services is the policy department responsible for, among other things, social security, family assistance, child support, child care and disability. Our office engages with DSS on many of these areas where we have questions or concerns about the way a policy is being administered by the relevant agency.

On occasion, DSS is responsible for directly administering payments or services to the public.

National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS)

The National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS), which commenced in 2008, is a partnership between the Commonwealth, state and territory governments which aims to increase the supply of new affordable rental housing and reduce rental costs for low and moderate income households by offering incentives to invest in dwellings. The scheme is administered by DSS.

Approved participants are entitled to an annual incentive in respect of each dwelling that satisfies certain NRAS requirements, such as letting the property at 20% or more below the market rent value. The incentive is either a cash amount or a tax offset certificate that is issued to the Approved Participant and then distributed to the individual investor who owns the property.

Approved Participants are usually property developers, not-for-profit organisations or community housing providers. NRAS is designed so that DSS has a direct relationship with the Approved Participants, but not with individual investors.

In early to mid-2014 DSS became aware that its administration of the scheme was not consistent with the regulations. DSS also assessed that a high proportion of the Approved Participants' claims for the 2013-14 NRAS year were likely to be refused.

DSS decided at it would be in the interest of investors, and in keeping with the intent of the scheme, to seek regulatory change before processing these claims. The regulatory amendments came into effect in late 2014.

These changes sought to allow greater flexibility, provide more generous timeframes for the lodgement of documentation evidencing compliance with the scheme and better align the regulations with policy and long-standing administrative practices.

While these changes intended to make it more likely that claims for the 2013-14 NRAS year would be successful, the process of amending the regulations delayed the assessment of these claims. Claim processing was further delayed when it became apparent that a significant proportion of claims were still non-compliant.

In October 2014 we started to receive complaints from investors in the scheme about the delays.

DSS has advised that it has also received an influx of complaints from investors (mainly individuals with a single dwelling in the scheme) who reported that the delay was causing them financial hardship. However, the design of the scheme has impacted DSS' ability to meaningfully engage with investors even though these are the individuals who are financially invested in the scheme.

DSS has endeavoured to communicate with investors via its website and has developed a letter for Approved Participants to sign so it can discuss individual claims directly with investors.

Throughout this time we have engaged in regular meetings and liaison with DSS to discuss the issues raised by the delayed processing of claims and the efficacy of the remedial measures the department implemented to address the issues. We have also engaged with the ANAO about its two-phase audit of DSS's administration of the scheme and continue to engage with DSS about ongoing issues flowing from the delay.

Indigenous Australians

Our office monitors complaints about Australian Government programs that specifically or predominantly impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, and particularly those living in remote communities. We also run an outreach program, focused on ensuring that our office remains accessible to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and that we are proactive in identifying issues with the administration of government programs which directly impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Outreach and engagement

This year we have expanded our engagement strategy by broadening our networks of community and government stakeholders across the country. We have continued to meet regularly with our established networks of community stakeholders in the Northern Territory, who have kept us informed about current issues affecting their Indigenous customers, who are predominantly from remote areas.

We have also started establishing stakeholder networks in capital cities around the country and have commenced a program of Indigenous roundtable discussion forums with these groups. This financial year we conducted a series of roundtable discussions in Brisbane, Canberra, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth and Sydney.

We met with a wide range of community stakeholders and advocates who work closely with the Indigenous community and we heard from them about key issues and problems affecting their clients.

In April in Darwin, in conjunction with the Northern Territory Ombudsman's office, we held Indigenous discussion forums focusing specifically on government complaint-handling systems for Indigenous individuals and communities.

We held separate forums with community and government stakeholders, who contributed their views about what works, what doesn't work, and possible solutions for improving government complaint systems so that they are both effective and accessible for Indigenous individuals and communities.

We intend to continue this dialogue with more forums over the coming year, with a view to encouraging government agencies to pursue more creative approaches in their dealings with Indigenous Australians in ensuring there are appropriate mechanisms to seek feedback and deal with complaints when delivering services and programs.

Two key areas of interest that we have continued to monitor closely are the Department of Human Services' (DHS) Centrepay and Income Management schemes.

Centrepay

Centrepay is a free bill-paying scheme for DHS customers. Over the years our office has received complaints and feedback about the scheme's administration, including problems which have contributed to detrimental outcomes for vulnerable customers, particularly Indigenous customers.

In 2013 DHS commissioned an independent review into the scheme. Our office was one of a number of stakeholders who made a submission to that review.

The Report of the Independent Review of Centrepay was submitted to the Secretary of DHS in June 2013. It made 89 recommendations for changes to the scheme. Our office has continued to engage with DHS about its response to the review since that time, including through our investigation of complaints raised with us on behalf of remote Indigenous customers.

In May 2015 DHS sought our office's views on aspects of its revised Centrepay framework and we provided our feedback in early June 2015. DHS has since published its responses to the independent review's 89 recommendations on its website, and it has also published its new Centrepay policy, which will begin to apply to businesses from 1 July 2015.

Our office welcomes DHS's restructuring of the Centrepay scheme, and particularly the changes aimed at limiting access to the scheme by business types which have historically been identified as predatory or exploitative, and improving the level of information provided to customers about their Centrepay deductions. However, we are yet to review the finer details of the new scheme, and have not yet been able to fully assess the extent to which the changes address the concerns previously raised by our office.

We will continue to monitor the rollout of the new Centrepay scheme and the impact of the changes through meetings and discussions with DHS and our stakeholder networks.

Income management

Income management (IM) is a scheme that enables DHS to manage at least 50% of a person's income support payments to ensure they meet their priority needs and those of their family. IM has applied in the Northern Territory since 2007 and has gradually been extended to other areas, and to new groups of DHS customers.

Despite these changes, the number of Indigenous customers being income managed still far outweighs the number of non-Indigenous customers, with 20,778 of 26,250 income-managed customers identifying as Indigenous as at March 2015.

Our office continues to monitor and investigate the scheme's administration through complaints and feedback we receive from our stakeholders and members of the public.

In September 2014 the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of New South Wales released the Final Evaluation Report, Evaluating new Income Management in the Northern Territory. The report, commissioned by the Department of Social Services, noted that new processes DHS had implemented in response to our office's 2012 own motion report into IM decision making had resulted in improvements to the IM exemption process, including:

…more stringent reporting about reasons for not allowing an application for an exemption, and new processes to ensure that customers subject to the compulsory income management measures are regularly informed of their right to apply for exemptions when engaging with Centrelink regarding other matters. Many of these changes were welcomed by the exemptions staff interviewed for the evaluation, and they noted they now felt clearer about the process and more comfortable in granting exemptions than before the Ombudsman's report:

There were a lot of exemptions being rejected at first because sometimes it wasn't always clear and there's a fine line of what we saw as being financially vulnerable. The Ombudsman came in and that led to changes in how we did documentation and assessed change. Now it's quite a process to reject an exemption. (Centrelink Customer Service Officer)2

The report also noted that our office's 2012 review had resulted in the tightening of guidelines around social worker assessments concerning customers on the vulnerable measure of IM.

The vulnerable measure of IM was originally designed to provide DHS social workers with an additional tool to use in supporting vulnerable or at-risk individuals who were financially vulnerable. The measure is applied to customers on a case-by-case basis, following an assessment by a DHS Social worker.

The vulnerable measure was expanded from 1 July 2013 to include an additional category of vulnerable customers who are not identified on a case-by-case basis, but rather by virtue of the fact they meet various objective criteria, making them part of a specific class or group. Vulnerable youth customers are identified by DHS's computer system and IM is automatically applied to them after they qualify for a trigger' payment.

In May 2015 the Australian Government introduced the Social Services Legislation Amendment (No.2) Bill 2015, which seeks to end case-by-case social worker identification of vulnerable welfare payment recipients (VWPRs), and to move to a system of identifying all VWPRs by virtue of their membership of a class or group of individuals, like the vulnerable youth measure.

The Bill was referred to the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee for inquiry and review and the committee tabled its report on 15 June 2015. Our office was one of a number of organisations and individuals who lodged submissions to the inquiry, cautioning against the removal of the case-by-case identification of vulnerable customers for income management.

Our office's position was based largely on our observations of the administration of the vulnerable youth measure of IM and, in particular, the use of automated decision-making processes.

In our view it has the potential to result in IM being applied to customers in circumstances where it could be detrimental to their wellbeing. Other organisations' submissions echoed our office's concerns in this regard.3

In addition to our submission, we have investigated a number of complaints about income management, resulting in some good outcomes.

CASE STUDY

The North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA) approached our office on behalf of three IM clients whose payments had been allocated by DHS towards items they claimed they were not required to pay for. In investigating those complaints, our office identified problems with DHS's process for recovering incorrect or overpaid IM funds from businesses, in cases where the business disputed the amount.We suggested that DHS consider reviewing its IM recall and recovery processes. DHS agreed with our suggestion and advised that it is developing new processes with ICT enhancements and updated procedures, which it expects to publish by October 2015.

These procedures will ensure that customers are provided with written notification about the outcome of their recall/recovery request and reasons, together with their review rights. We are pleased with DHS's response and will continue to monitor this issue.

CASE STUDY In 2014 NAAJA approached our office on behalf of two IM clients to complain that, following a successful application for debt waiver, a DHS Authorised Review Officer (ARO) had informed NAAJA that DHS would repay the amounts their clients had overpaid towards the waived debts into their IM accounts rather than their personal bank accounts.

NAAJA complained that the debts were initially raised before the commencement of IM, and that their clients had repaid a significant portion of the debts from their personal funds. Therefore, it wasn't fair that their access to the refunds should be limited by the money being repaid to their IM accounts.

NAAJA advised that although DHS ultimately agreed to refund the money to their clients' personal bank accounts, they and other legal services had previously dealt with similar cases where there appeared to be a degree of uncertainty about what account the money should be paid into for IM customers following debt-waiver decisions. NAAJA raised concerns about the lack of a clear position from DHS, including the likelihood of unfairness in similar cases.

In response to our investigation, DHS advised our office that its policy is to repay amounts to IM customers' personal bank accounts in all cases following successful debt-waiver decisions. DHS acknowledged that the advice its staff provided to NAAJA on this point was incorrect.

In responding to our initial inquiries, DHS provided our office with a copy of its internal procedures outlining what steps its staff should take when refunding payments on debts.

DHS advised that the staff involved in processing debt refunds were aware that they should refund these amounts to IM customers' personal bank accounts, and those staff had received training about this. However, the written procedures did not make it clear that payments would be refunded to IM customers' personal bank accounts.

We pointed out that the lack of a clear written policy in DHS's Operational Blueprint meant that the correct process might not be clear to other DHS staff such as AROs, who may have cause to discuss refunds with customers in the course of explaining their decisions.

We therefore suggested that DHS update its procedures to make this clear, in order to avoid any future confusion over this issue. The department agreed with our suggestion and has updated its internal procedures to state that refunds of over-recovered debts to IM customers will be refunded to the customer's personal bank account.

POSTAL INDUSTRY OMBUDSMAN

Overview

The Commonwealth Ombudsman is also the Postal Industry Ombudsman (PIO). The PIO role was established in 2006 to provide an industry ombudsman service for postal operators and their customers.

Australia Post is a mandatory member of the scheme, while private postal operations (PPOs) can register voluntarily. As at 30 June 2015, there were six PPOs registered.

The PIO can investigate complaints about postal or similar services provided by Australia Post and PPOs. The Commonwealth Ombudsman can also investigate complaints about administrative actions and decisions taken by Australia Post. Most commonly, people complain to the PIO about lost letters or parcels, delivery issues (including the failure to attempt delivery of parcels and incorrect safe drop procedures), and dissatisfaction with Australia Post's handling of their complaint.

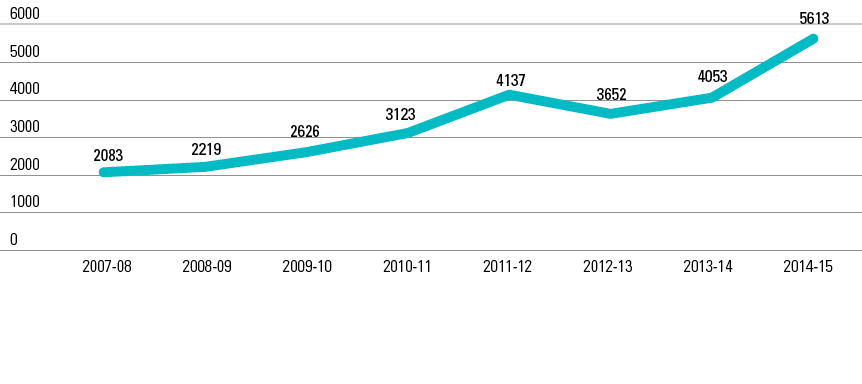

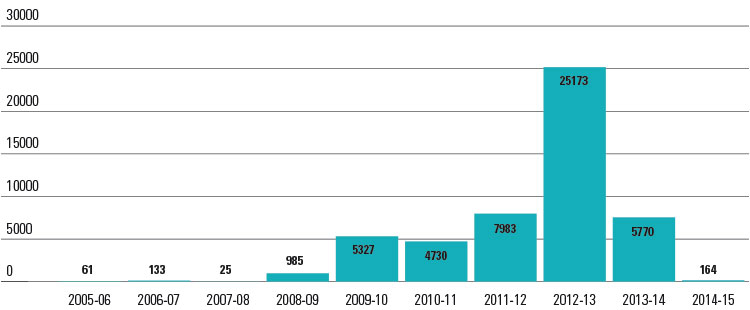

Figure 2 All approaches for Australia Post (Commonwealth & PIO)

Statistics

In 2014-15 we received 5613 complaints about Australia Post, which was a 38% increase on the previous financial year. In general, the volume of complaints about Australia Post has been steadily growing and has almost tripled since the PIO was established in 2006.

During this financial year Australia Post complaints represented around 27% of the total number of in-jurisdiction complaints received by the office, making Australia Post the second most complained about entity in our jurisdiction. However, we acknowledge that Australia Post also has a very high level of daily contact with the public.

Australia Post reported that it delivers more than 16 million articles of mail each day to over 11 million addresses and serves approximately 70,000 customers in-store daily.

We also received 16 complaints about other postal operators in the PIO jurisdiction, which was 60% more than the previous financial year. These complaints, together with the 5351 complaints we received about Australia Post in the PIO jurisdiction, totalled 5367 complaints in the PIO jurisdiction. This was an increase of almost 40% on the previous financial year.

We did not investigate all complaints we received about Australia Post or PPOs. The main reasons for declining to investigate a complaint included that:

- the complaint was outside our jurisdiction (for example, it was about employment or a company that was not a registered PPO)

- the complainant could not show they had made a reasonable attempt to resolve the issue with Australia Post or the PPO

- we assessed that a better practical outcome was unlikely.

Where we assessed that Australia Post could consider providing a better outcome, we transferred the complaint to Australia Post for reconsideration (a second-chance transfer, as described below).

Of the approaches we received about Australia Post and PPOs in 2014-15, we commenced 468 investigations. In total, we completed 428 investigations during this period (392 under the PIO jurisdiction and 36 under the Commonwealth Ombudsman jurisdiction). Only two of the investigations completed during this period related to a complaint about a PPO, with the remainder concerning Australia Post.

Second-chance transfers

We transferred 1973 complaints (around 35% of complaints received) to Australia Post for reconsideration pursuant to our second-chance transfer arrangement. These were relatively uncomplicated complaints where we assessed that Australia Post could consider offering a better outcome to the complainant.

In general, this process gives Australia Post another opportunity to review the complaint and resolve the matter, which potentially reduces the need for an Ombudsman investigation. Further, the outcome of a referral back to Australia Post is typically a quicker resolution of the issue for the complainant and an opportunity for Australia Post to learn from complaints to further improve its own complaint-handling practices.

Most of the complaints transferred as part of this arrangement were successfully resolved by Australia Post. However, complainants can return to our office if they are dissatisfied with the response. We recorded a small number of complaints (196, or around 10%) as returning to our office following a transfer. We investigated a small proportion of these complaints, but we were generally satisfied with Australia Post's response and declined to investigate.

Fees

The PIO was established with the intent to recover its costs from the industry by charging investigation fees. Fees are calculated and applied retrospectively after the end of the financial year and are returned to Consolidated Revenue.

Significant issues in the reporting period

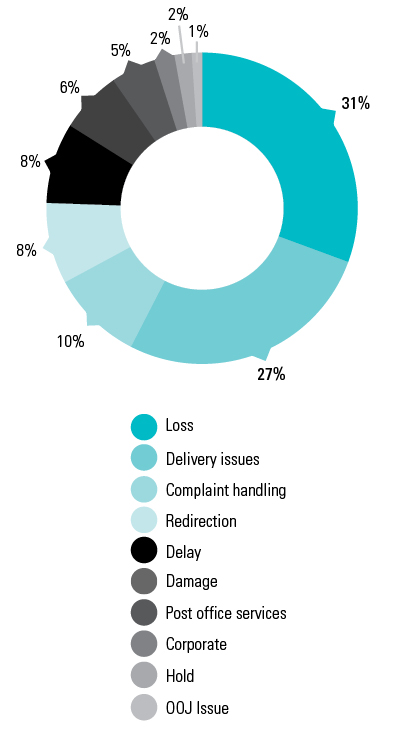

At the beginning of the financial year we altered the way we record complaints about Australia Post and PPOs in order to better capture the root cause of complaints. Following this, we identified loss, delivery issues and complaint handling as the three most common top-level complaint issues about Australia Post.

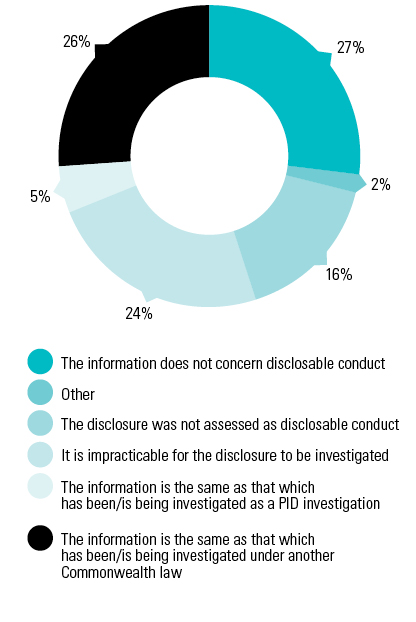

Figure 3 Top level issues closed by Australia Post 2014-15

1. Loss

The most common complaint received by the PIO relates to lost letters or parcels. In these cases the dispute typically arises because Australia Post believes it has correctly delivered an article, but the addressee claims that they have not received it.

CASE STUDY

Catalina posted 105 envelopes at her local Post Office at a cost of $1.40 per envelope. After hearing that some addressees had not received the item, she contacted each of the 105 addressees and found that none of them had received it. Catalina complained to Australia Post and requested compensation for its failure to deliver the envelopes. Australia Post declined to compensate Catalina, advising her that as per its terms and conditions, no compensation is payable in relation to ordinary mail articles. In response to our investigation, Australia Post advised that mail volumes at the time of posting were larger than normal and the items may have been delayed rather than lost. However, Australia Post recognised the financial loss and inconvenience caused, and therefore provided Catalina with a discretionary payment for the total cost of postage ($147).

2. Delivery issues

Delivery issues are broad-ranging and include complaints about the failure to attempt delivery of parcels, incorrect safe-drop procedures and the failure to obtain a signature on delivery when required to do so.

CASE STUDY

Ivan purchased an item online and the seller sent it to him by Express Post. Ivan did not receive the item but the tracking information indicated that the parcel had been delivered. When Ivan complained to Australia Post, he was advised that the parcel was correctly delivered as it was dropped at a safe place at his address, and the complaint was closed. In response to our investigation, Australia Post decided the address was not a suitable location for a safe drop due to visibility from the street. Australia Post provided Ivan with full compensation for the item and the location was no longer deemed a safe drop location.

3. Complaint handling

Complainants often explain to the PIO that they attempted to resolve their complaint with Australia Post, but were dissatisfied with how their complaint was handled. Reasons for dissatisfaction most often included unreasonable delay or a lack of response, or conflicting or confusing advice provided by Australia Post.

CASE STUDY

Akram posted a computer hard drive to a client and paid for Extra Cover (up to $300). Online tracking showed that the item reached a point in transit and did not go any further. Akram lodged a complaint and a claim with Australia Post. Australia Post advised Akram on several occasions that his complaint was under investigation; however, after six weeks it had not provided a formal response or assessed his claim. During this period Akram's client notified Akram of its intent to sue for damages as the hard drive contained sensitive commercial information. As Australia Post had not advised Akram of the outcome of its investigation, Akram elected to pay his client $1200 compensation in order to avoid litigation. In response to our investigation, Australia Post advised that it was unable to locate the missing hard drive and deemed it lost. Akram was satisfied with the compensation offered by Australia Post as a result of our investigation.

Introduction of new services

In addition to the common complaint themes outlined above, we identified two critical events that led to a spike in complaints during 2014-15:

1. Introduction of new complaints management system, MyCustomers

Australia Post introduced its new complaints management system, MyCustomers, in late 2014. Australia Post experienced some early technological problems with this new system, which resulted in a backlog of complaints and some delays. This in turn led to a rise in complaints to the PIO about Australia Post's complaint handling.

A key aspect of MyCustomers is that it sends auto-generated emails to complainants advising when their complaint has been received, progressed and eventually closed. Complainants approached the PIO advising that they had received notifications that their complaint had been closed without any information or contact from Australia Post in response to their complaint. Issues associated with auto-generated emails have also affected complaints transferred from the PIO to Australia Post via our second-chance transfer arrangement, as well as Ombudsman investigations.

We are liaising with Australia Post as it attempts to resolve issues associated with the new MyCustomers system, particularly its use of auto-generated emails.

2. Introduction of new service, ShopMate

In October 2014 Australia Post launched its ShopMate service to assist customers who want to purchase goods from sellers in the USA who do not offer shipping to Australia. Subscribers to the service can shop directly with US merchants and have their goods sent to an Australia Post logistics warehouse in the USA. Australia Post then advises the customer of the cost to forward the purchased goods to a delivery address in Australia and once costs are paid, Australia Post sends the goods to the addressee in Australia.

The PIO received 83 complaints about ShopMate during the year. The key issues related to disputes about the dimensions of the relevant article and whether it exceeded ShopMate's size limits, a lack of clarity regarding pricing calculations and delivery problems that occurred before arrival at Australia Post's warehouse.

PIO investigations have demonstrated that it is often difficult for a customer to know the exact dimensions of an article before purchase, and the customer is most likely uninformed about the manner in which the merchant will pack the goods. The result is that, once Australia Post has received the item in its US warehouse, the customer may be surprised and unhappy with Australia Post's advice regarding the cost of shipping (or, in some cases, the refusal to ship the item to Australia due to it exceeding the ShopMate size limits).

CASE STUDY

Mei ordered a Christmas present for her child from a US merchant, to be delivered via the ShopMate service. After it arrived at the US warehouse, Australia Post advised Mei that the item was over the size limits and could not be shipped to Australia. Mei complained to Australia Post, noting that the dimensions of the item on the merchant's website suggested that the item was within the advertised limits. Australia Post responded that, despite the information on the merchant's website, the length of the article exceeded the size limits, and Mei was provided with the options of having the item destroyed for a $5 fee, returned to the sender (at Mei's expense) or sent to another US address (at Mei's expense).

Mei requested that Australia Post repack the item to reduce the length; however, Australia Post advised that it had already repacked the item but it could not reduce the length. Mei complained to the PIO stating that Australia Post's responses did not satisfactorily explain the discrepancy in the length of the item, and that delays in responding to her were preventing the issue from being resolved in time for Christmas. Following our investigation, Australia Post arranged for the article to be delivered via an alternative method at a discount as a gesture of goodwill in recognition of the disappointment Mei experienced in not receiving the goods in time for Christmas.

At this point the customer has already paid the US merchant for the goods, but may only be left with the options of paying to have the item destroyed, returning it to the sender or arranging for an alternative method of delivery at their own cost.

We are liaising with Australia Post to develop a better understanding of the key complaint themes and to develop a position regarding issues associated with this new service.

Reforming Australia Post

The growth in electronic communications and changes in consumer behaviour have recently presented Australia Post with significant challenges. In early 2015 Australia Post communicated that the number of letters delivered by household had fallen by one-third since volumes peaked in 2008, resulting in Australia Post's letters business losing more than $300 million a year.

In March 2015 the Federal Government approved Australia Post's request for regulatory reform of its letters service. As a result, it is expected that a two-speed letters service - a priority and a regular service - will be introduced for consumers no earlier than September 2015. The new regular service will provide the cheapest option for consumers and will be delivered two days slower than the current timetable, while the priority service will be appropriate for consumers wanting to send mail at the current schedule. This announcement led to Australia Post commencing a nationwide consultation process, with the aim of engaging employees, customers and government on the implementation of the changes.

We recently participated in an interdepartmental committee chaired by the Department of Communications on the modernisation of Australia Post. Our broad complaint-handling experience across the public sector gives us a unique insight into public administration and we have sought to use that perspective to ensure that the potential impacts on Australia Post's customers are taken into account.

Particular areas of interest for the PIO include the possible increase in complaints and the flow-on effects on the communication between government agencies and their clients, particularly the vulnerable and disadvantaged members of the community. We will continue working with Australia Post during the transition to the new two-tier letters service.

Commitments from 2013-14

In the past we have observed that information provided by Australia Post should help customers understand their rights and responsibilities, and to understand which service is best suited to their needs. In our last Annual Report we identified some issues that could be improved. The progress made in 2014-15 in relation to some of these issues is noted below:

- Adequate packaging - Packaging is a significant factor when deciding whether or not to pay compensation for damage and we are pleased that Australia Post has improved the information it provides regarding how to pack different types of items. In particular, Australia Post revised its Dangerous and prohibited goods and packaging guide in December 2014. However, we will monitor this issue in the coming year as we continue to receive complaints regarding the adequacy of packaging materials.

- Compensation - We have previously noted that there was a potential conflict in information provided by Australia Post about the compensation payable for coins lost or damaged in the post. Australia Post clarified its position on this issue in its terms and conditions and Dangerous and prohibited goods and packaging guide to consistently explain that Australia Post prohibits coins in the International Post and all services within Australia except Registered Post, or a parcel service in conjunction with Extra Cover and Signature on Delivery, where the face value of the coins is A$200 or less in any one consignment.

CASE STUDY

Emmanuel arranged for a parcel to be sent to him using Australia Post's cash-on-delivery service with Extra Cover. At the time of collection of the parcel, Emmanuel noticed that it was wrapped in a postal bag. When he opened the postal bag, the contents of the parcel fell out and he found a note explaining that the parcel had been repackaged by Australia Post because the packaging had been damaged at the delivery centre. Emmanuel then found that some of the items he was expecting to receive were missing from the parcel and he contacted Australia Post to make a claim for compensation (noting that the sender had explained to him that Australia Post staff had originally assisted with the packaging of the items).

Australia Post refused Emmanuel's claim for compensation because it believed that the items were not adequately packaged. In response to our investigation, Australia Post concluded that although the packaging did not meet Australia Post's packaging recommendations in this instance, the packaging was processed as sufficient by the staff member who completed the postage transaction. Based on this, Australia Post agreed to compensate Emmanuel for the lost items in accordance with the Extra Cover purchased.

- Tracking - We sometimes receive complaints that parcels were not fully tracked and therefore complainants are unable to check and confirm lodgement, progress and delivery of an item. While Australia Post aims to scan parcels at key points in the delivery process, we recognise this may not always occur, usually due to infrastructure limitations or human error. In the past we discussed with Australia Post the importance of providing clear public information about the tracking service and what it offers. The situation has improved as Australia Post has rolled out increased infrastructure to support its tracking capabilities, and the information currently provided by Australia Post better explains the scope of tracking.

- Authorisation, signatures and identification - Australia Post's identification checks and verification of authority are common areas of dissatisfaction associated with complaints about unauthorised mail redirections, parcels being released to the wrong person and authorisation to leave signature items at an address. We have previously approached Australia Post with our concerns about its policy and procedures, and we recently pursued this issue further by suggesting that Australia Post consider:

- clarifying in its procedures manual the nature of possible arrangements that Australia Post may make to release a non-signature item to a regular customer known to staff in circumstances where staff have checked the person's identification in the past

- clarifying in its procedures manual the principle that that Australia Post accepts signed authorities “in good faith†(given that it is unable to verify the addressee's signature), as well as providing further guidance in relation to how staff can satisfy themselves that an authority is genuine

- reviewing the information Australia Post records to demonstrate that identification has been checked (as Australia Post does not currently record any identification details)

- reviewing the information provided in collection cards to ensure they are consistent in regards to authorisation instructions.

Major outcomes

The PIO carries out its functions by investigating individual complaints, identifying and pursuing systemic problems, and acting on emerging issues.

A number of our investigations have resulted in better outcomes for complainants including expedited action, comprehensive searches for lost items, apologies, compensation payments, postage refunds, staff being counselled or disciplined, and the provision of better explanations by Australia Post or our office.

CASE STUDY

Nora had not received any mail since moving in to her new residence and believed her mail was being delivered to her next door neighbour's letterbox instead. Nora complained to Australia Post and received conflicting advice about why her mail was being delivered incorrectly and whether her address was a valid delivery point. Our investigation found that until recently Nora's residence had a different street address and the new address was not listed on the National Address File (NAF). The result was that staff at the local delivery centre were unaware of the delivery location. Australia Post updated Nora's address on the NAF, informed the local delivery centre of the change and apologised to Nora for the inconvenience.

Our investigations and ongoing engagement with Australia Post in relation to key complaint issues has also resulted in improvements to Australia Post's policies, procedures and communications. For example, the PIO was provided with opportunities to comment on Australia Post's proposed updates to its postal guides. In particular, we provided comments in relation to Australia Post's Domestic Parcels Guide, and we are also liaising with Australia Post regarding updates to its General Post Guide.

Taxation ombudsman

Final Taxation Ombudsman report

In March 2015 the Parliament passed legislation that transferred the Commonwealth Ombudsman's tax complaint-handling function to the Inspector-General of Taxation (IGT), on 1 May 2015.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman is no longer able to investigate new complaints about the Australian Tax Office (ATO) or the Tax Practitioners Board (TPB), except for complaints about freedom of information (FOI) or public interest disclosure (PID).

This Annual Report will be our last report on the activities of the Taxation Ombudsman; however, PID and FOI matters concerning the ATO or TPB may be reported separately.

The handover of the tax complaints function to IGT was successfully completed and with the least possible inconvenience to taxpayers.

Overview

This year marks the 20th anniversary as well as the end of the Taxation Ombudsman role.

The role was established in 1995 to increase the focus on the investigation of complaints about the ATO and since then we have finalised more than 40,000 complaints.

Major events or projects undertaken by the ATO that proved to be sources of complaints during this period related to:

- the ATO's handling of complaints about the settlement process for taxpayers involved in mass marketed investment schemes in 1998-99

- the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax in 2000-01

- the rollout of the ATO's systems upgrade (referred to as the change program') in 2009-10 and the impact of delays on taxpayers

- the Project Wickenby joint taskforce and the ATO's handling of complaints from high-profile taxpayers in 2012-13.

The Taxation Ombudsman completed several own motion investigations during this period, which led to significant change and service improvement including:

- an investigation into ATO complaint handling, published in July 2003. This led to the creation of a whole-of-ATO complaints management system with over 66% of complaints resolved satisfactorily

- the ATO's administration of garnishee action, published in April 2007. As a result the ATO improved its procedural advice and guidance to staff and introduced an internal review process for payment arrangement decisions

- re-raising of written-off tax debt, published in March 2009. The ATO improved its advice to taxpayers to avoid confusion over the debt re-raise process

- resolving Tax File Number compromise, published in September 2010. The ATO changed its identification and response processes to improve outcomes for taxpayers.

Over the past 20 years we worked proactively with the ATO to encourage it to improve its complaint-handling process, learn from complaints and take active responsibility for resolving them. The ATO has been receptive to our approach and adopted many of our suggestions, resulting in an enhanced experience for taxpayers in resolving matters.

This approach resulted in a steady decline of complaints to the Ombudsman about the ATO, and this year the Taxation Ombudsman received the lowest number of annual complaints since the commencement of the role in 1995.

Following is a summary of 2014-15 complaint matters concerning the ATO.

Complaints about the ATO

The majority of complaints to the Ombudsman about the ATO are made by individual taxpayers and small-business owners.

In 2014-15 we received 1118 complaints about the ATO, the lowest number of complaints received in any year since the Taxation Ombudsman was established, and a decrease of around 18% compared to 2013-14 (1369). This reduction is mostly attributed to the fact that we stopped receiving tax complaints about the ATO from 1 May 2015.

Overall, complaints about the ATO accounted for over 5% of the total number of in-jurisdiction complaints received by the Ombudsman during the year.

Complaint themes

During 2014-15 the most common complaints received by the Ombudsman about the ATO related to:

- debt-collection activities

- lodgement and processing of income tax returns

- audits and reviews conducted by the ATO

- superannuation.

Debt collection

Concerns regarding the ATO's debt-collection activities continue to result in a significant number of complaints to the Ombudsman, accounting for over 20% of complaints received about the ATO in 2014-15.

The most common theme raised by complainants related to garnishee action. In some cases complainants were unaware of an ATO debt or the ATO's intention to garnishee a bank account or income tax refund until after the garnishee action was taken.

This issue can arise when a taxpayer has multiple tax accounts with the ATO and may not update new contact details on each account. The ATO enhanced communication to taxpayers regarding the need to update contact details on all tax accounts; however, this remains a persistent cause of complaints.

CASE STUDY

A debt collection agency contacted Mr and Mrs X about an unpaid ATO debt in relation to non-payment of PAYG instalments for their business. They complained to the ATO that it had not made contact with them before referring a debt to a collection agency. As a result of investigation by this office, it was established that Mr and Mrs X had updated their personal address but not the business postal address with the ATO, and all correspondence relating to PAYG instalments were sent to a previous address. The ATO wrote to Mr and Mrs X and explained the circumstances under which the debt arose, updated the address and confirmed the amount and due date of the remaining debt.

Lodgement and processing

The annual lodgement of income tax returns and activities involving the ATO's Income Tax Return Integrity (ITRI) program continued to be the subject of a significant number of complaints to the Ombudsman, particularly during tax time. In 2014-15 complaints involving issues with lodgement and processing accounted for around 18% of complaints received about the ATO.

The ITRI program detects income tax returns that may contain missing or incorrect information. This can trigger a review of the income tax return before a refund is issued, which can lead to a delay in issuing a refund even if the ATO ultimately determines that the taxpayer's information is correct.

The ATO has significantly improved taxpayers' experience with the ITRI program following feedback from this office, and continues to improve its communication with taxpayers and agents regarding delays.

CASE STUDY

Ms X currently resides overseas but lived and worked in Australia for a period beginning in 2012. Ms X lodged her 2013 tax return and received a debt assessment. She later lodged her 2014 tax return and received a refund by cheque. As she lives overseas she was unable to deposit or cash the cheque, so she requested that the ATO cancel the cheque and instead credit the funds towards her tax debt. The ATO informed Ms X that it would review her status as a non-resident. Ms X was concerned that the ATO was charging her interest on the unpaid debt and any delay would cause further cost. She felt the review and subsequent delay was unfair. Ms X complained to the ATO but found its responses unclear. In the course of our investigation, the ATO reviewed its actions and resolved Ms X's concerns. The ATO advised Ms X that it agreed with her residency status and had not applied a general interest charge. The ATO cancelled the tax refund cheque and applied the credit to the debt.

Superannuation

In 2014-15 over 10% of ATO complaints we received related to superannuation and unpaid superannuation guarantee payments. Complaints were typically made by individual employees regarding unpaid superannuation, with concerns about delay, lack of information and uncertainty about the ATO's actions the most common complaint themes.

Changes to regulations for Self-Managed Superannuation Funds (SMSF) resulted in a small number of complaints from SMSF trustees, most commonly concerning a refusal by the ATO to approve the registration of the SMSF.

CASE STUDY

Mr X applied to register an SMSF with the ATO. The ATO audited Mr X's application and, as a result, decided to withhold the Australian Business Number (ABN) of the fund from the Super Fund Look Up website. Mr X complained to the ATO about the decision, and the ATO's advice that no appeal avenues were available to challenge the decision. Unsatisfied with the ATO's response to his complaint, Mr X approached this office. Mr X stated his original concerns with the decision and lack of appeal avenues, noting his view that the response from the ATO did not adequately justify the grounds for its decision. Following an Ombudsman investigation, the ATO wrote to Mr X explaining its regulatory obligations and decision-making processes in assessing an SMSF application, and the subsequent review it conducted after Mr X's formal complaint. The ATO also clarified that the decision is not subject to the usual external administrative appeal mechanisms but that he may seek redress through the courts.

Audit and review

Approximately 8% of tax complaints received by the Ombudsman in 2014-15 involved concerns about the ATO's audit activities, most commonly in relation to income tax returns. When the ATO identifies that an income tax return or GST claim may contain incorrect or incomplete information, it may subject the claim to a thorough review before issuing a refund.

Complainants commonly raised concerns regarding the selection of their income tax return for audit, and the length of time taken to finalise the audit. Other complaint issues included the ATO's decision to extend the scope of audit to previous years, and problems with the volume and types of documentation the ATO has requested in relation to the audit.

CASE STUDY

Mr Y's tax return was audited and the ATO gave him 21 days to provide documents and receipts to substantiate his deductions, but he was unable to provide the information within that timeframe. The ATO granted an extension of time but he was still not able to provide the information in time, due to significant personal circumstances. The ATO refused to grant a further extension and amended his return accordingly. Mr Y complained that he felt the ATO ignored his circumstances and that he didn't agree with the audit decision. Our investigation revealed that the ATO extension decision was reviewed by a senior officer and it had allowed Mr Y approximately 50 extra days. The ATO had also made several unsuccessful attempts to contact him. Mr Y can correct the final assessment by providing the documents via the objection process.

Other matters

Social media - the Taxation Ombudsman Facebook page

In August 2014 we launched the Taxation Ombudsman Facebook page to provide taxpayers with real-time information concerning the progress of Tax-Time and other tax complaint information. The Facebook page proved a popular addition with posts shared widely, particularly by individual tax agents.

myGov and the ATO's electronic lodgement process

myGov is a service managed by the Department of Human Services (DHS). It allows users to access a range of Australian Government services with one username and password. From the 2013-14 tax year, taxpayers are required to link their ATO account to myGov in order to lodge their tax return electronically.

While we received some complaints about myGov, the majority raised general concerns with the requirement to register with myGov rather than the operation or use of the service.

Immigration Ombudsman

Overview

The Immigration Ombudsman has continued its oversight of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) through:

- regular inspection of immigration detention facilities

- monitoring of immigration compliance activities and those detained and later released as lawful non-citizens

- reporting to the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection on the circumstances of people who have been in immigration detention for more than two years

- investigating individual complaints about general immigration matters and detention.

Complaints

We deal with immigration complaints in two streams: general immigration (visas and citizenship) and detention-related matters. We received 1810 complaints about the department in 2014-15, compared with 1771 in 2013-14, an increase of 2%. We investigated 282 complaints, or 16%.

We received 806 complaints about detention-related matters and completed 188 investigations. We received 1004 general immigration complaints and completed 94 investigations. This includes some investigations commenced in the previous financial year.

We have seen the same issues in general immigration complaints as in previous years. The largest category of complaints was delays in visa application processing. The second largest was complaints about delays or the refusal of citizenship applications.

Complaints from people in immigration detention about safety and security have increased, as have those about assault and the use of force.

Medical issues are also a cause of ongoing concern. This includes complaints about the provision of medication and access to specialist medical and dental treatment.

Similarly, property issues are a common area of complaint, including detainees' property going missing or not being transferred when detainees are moved within the detention network, as well as complaints about compensation claims for lost or damaged property. Our detention inspections team continues to focus on this issue as part of its inspection of detention facilities.

The department's response times for complaint investigations continues to be a concern. For the first six months of 2014-15, only 38% of responses were received within the agreed timeframe of 28 days, with 58% taking between 29 and 60 days. There was a marginal improvement in the second six months with 40% taking less than 28 days and 50% taking between 29 and 60 days. Ten percent of complaints took longer than 60 days to receive a response. We are continuing to work with the department to improve this process.

Warm transfer of complaints to the department

Where a person who complains to us, has previously complained to the department and is not happy with the outcome, we offer them a warm transfer' that refers the complaint back to the department, giving it a second opportunity to resolve the matter without investigation by this office. In 2014-15 we transferred 68 complaints to the department.

Stakeholder engagement

We host a series of community roundtables in Australian capital cities to strengthen our engagement with stakeholders in the immigration sphere. These roundtables are an opportunity to inform stakeholders, including representatives from service providers, non-government organisations, advocacy groups and asylum seekers, about the role of the Ombudsman and to listen to any concerns about the administration of the department's functions.

To continue this engagement we have also begun publishing a quarterly e-newsletter to share news about our priorities and issues of interest.

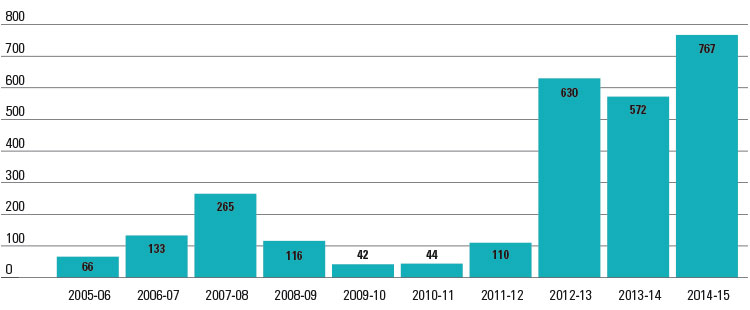

Liaison