Annual Report 2010-11 | Chapter 5

Chapter 5

Agencies overview

- Agencies overview

- Commonwealth Ombudsman

- Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

- Centrelink

- Child Support Agency

- Comcare

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

- Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency and Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

- Department of Health and Ageing

- Fair Work Ombudsman

- Medicare Australia

- Monitoring and Inspections

- Freedom of Information

- Indigenous programs – Closing the Gap in the Northern Territory

- Feature – Improving agencies’ use of Indigenous Interpreters

- Defence Force Ombudsman

- Department of Defence and the Australian Defence Force

- Department of Veterans’ Affairs

- Defence Housing Australia and Toll Transitions

- Feature – Defence Portfolio Agencies Forum

- Immigration Ombudsman

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship

- Feature – Immigration Detention – visits program

- Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- Law Enforcement

- Australian Federal Police

- Australian Crime Commission (ACC)

- Attorney-General’s Department

- Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI)

- CrimTrac

- AUSTRAC

- Feature – Australian Federal Police/Ombudsman Forum

- Overseas Students Ombudsman

- Overseas Students

- Feature – Safety net for overseas students

- Postal Industry Ombudsman

- Postal Industry

- Feature – Role of the Postal Industry Ombudsman

- Taxation Ombudsman

- Role

- Australian Tax Office

- Australian Prudential and Regulation Authority

- Australian Securities and Investments Commission

- Tax Practitioners Board

- Insolvency and Trustee Service Australia

- Feature – Tax Institute National Convention

Agencies overview

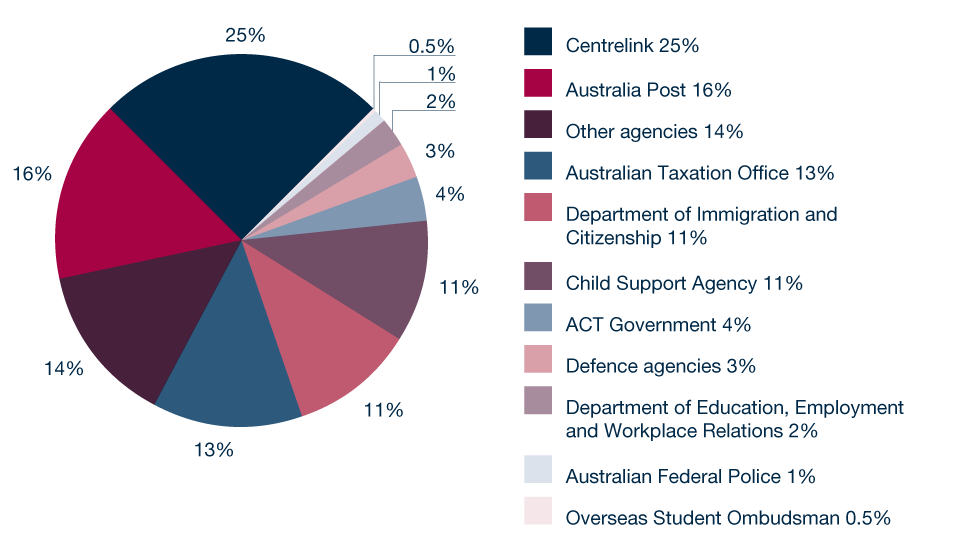

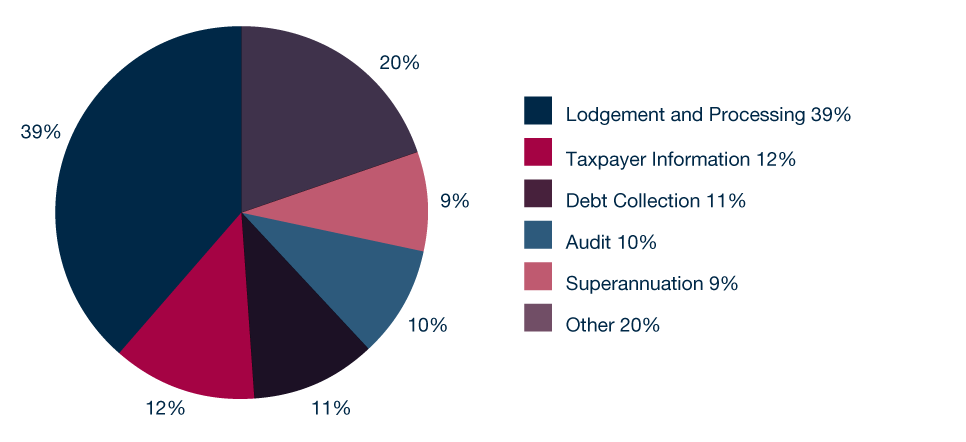

Most of the approaches and complaints received by the Ombudsman’s office within its jurisdiction related to the following individual Australian Government agencies:

- Centrelink (4954)

- Australia Post (3123)

- Australian Taxation Office (2589)

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2137)

- Child Support Agency (2121)

- ACT Government (742)1

- Defence agencies (638)

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (481)

- Australian Federal Police (207)

The Overseas Students Ombudsman jurisdiction received 161 complaints and approaches. A further 2734 complaints and approaches were received about other Australian Government agencies.

Figure 5.1 represents the above figures in percentage terms.

This chapter assesses our work with agencies in handling complaints and dealing with broader issues during 2010–11. It also discusses the monitoring and inspection work we undertake and complaints arising from the way agencies deal with freedom of information requests.

The chapter is divided into seven sections dealing with the Ombudsman’s jurisdictions at the Commonwealth level.

These jurisdictions are:

- Commonwealth Ombudsman

- Defence Force Ombudsman

- Immigration Ombudsman

- Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- Overseas Students Ombudsman

- Postal Industry Ombudsman

- Taxation Ombudsman.

More detailed information by portfolio and agency is provided in Appendix 3— Statistics .

Figure 5.1: Proportion of approaches and complaints received within jurisdiction 2010–11

- Figures that relate to the ACT Ombudsman jurisdiction have been included in this annual report to provide an indication of workflow. A separate ACT Ombudsman Annual Report has also been prepared for the ACT Parliament.

Commonwealth Ombudsmen

Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

Overview

The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (Customs and Border Protection) regulates the security and integrity of Australia’s borders.

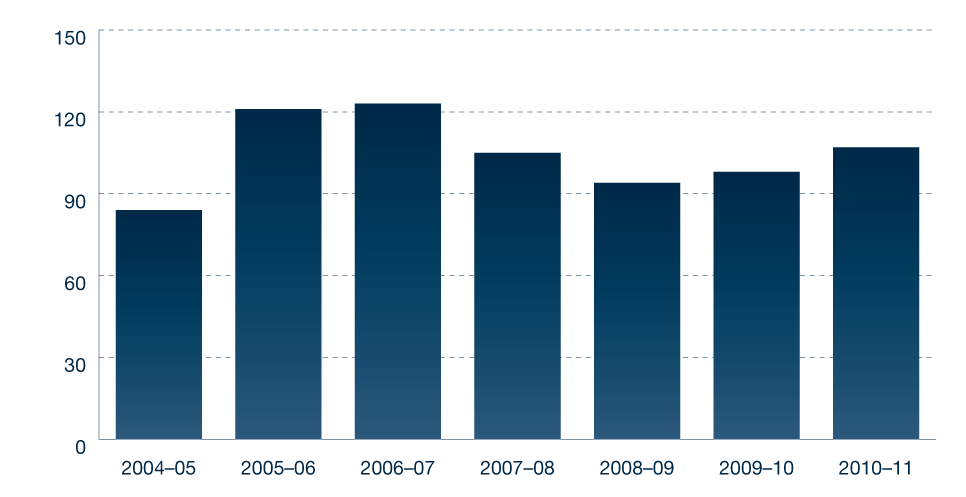

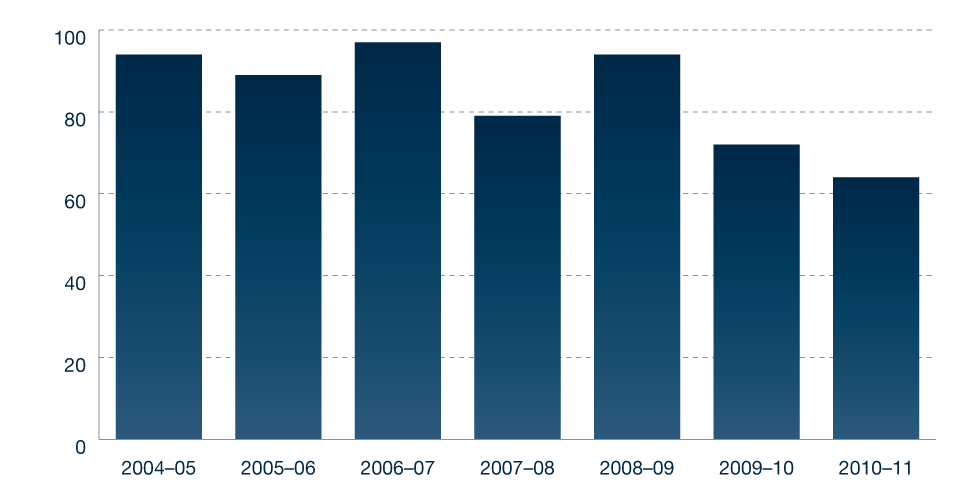

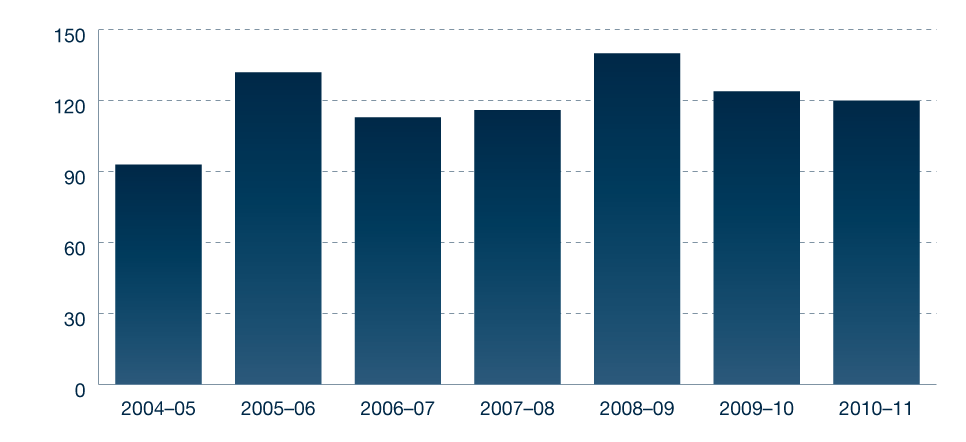

The Commonwealth Ombudsman received 107 approaches and complaints about Customs and Border Protection this financial year. This was a slight increase on the 2009–10 financial year, in which we received 99 complaints. There was a decrease in passenger processing complaints from the previous year.

As well as investigating individual complaints, we also published an own motion report into the use of coercive powers in passenger processing, and scrutinised the implementation of new passenger screening arrangements.

Figure 5.2: Customs and Border Protection approach and complaint trends 2004–5 to 2010–11

Complaint themes

Our office receives complaints on a diverse range of issues about Customs and Border Protection. The most common themes this year were the importation of goods (relating to seizure decisions in particular), complaint handling issues and the exercise of powers relating to the processing of international air passengers.

We have noted significant media interest in the proposed introduction of new screening technologies and processes affecting international air passengers. We expect this to be an area of continued public interest and possible complaint to our office, and will monitor this in the year ahead.

Customs and Border Protection has a robust complaints system and undertook to review that system for airports in particular, following the identification of some areas for improvement during our investigation of a complaint finalised early this year. These areas included the inadequate provision of information at airports about how to make a complaint, limited requirements to document complaints in the airport environment and a lack of clear procedures specific to handling complaints at airports. Given the significant powers exercised by the agency in the busy and often pressured environment of an airport, it is important that complaints are encouraged and properly handled.

Reports or submissions released

In December 2010 the Commonwealth Ombudsman released an own motion report on the administration of coercive powers in passenger processing. The report was well received by Customs and Border Protection and most of the recommendations made were accepted. The purpose of the report was to provide external scrutiny of the use of strong coercive powers (for example to question, examine baggage, copy documents and retain possessions for further examination) and to ensure proper checks and balances are in place.

Our recommendations were substantially implemented by the end of the financial year. The outcomes of that process can be seen in improvements to internal training, policies and procedures used by officers exercising strong coercive powers in the processing of international air passengers. We will continue to monitor complaints and liaise with Customs and Border Protection to assess the outcomes of the own motion report and any further areas for improvement.

Systemic issues

Our investigation into the exercise of Customs and Border Protection’s coercive powers (Australian Customs and Border Protection Service: Administration of coercive powers in passenger processing – December 2010) identified issues with the information provided to people whose possessions are retained by Customs to check whether they are prohibited. Typically complaints have related to the retention of mobile phones, laptops and other electronic storage devices, which require forensic examination by Customs before a seizure decision can be made. Changes are currently being implemented by Customs and Border Protection to ensure adequate information is provided to the person and that items are returned as quickly as possible (if the item is not seized). Complaints to our office since the own motion investigation suggest this is no longer a prevalent issue – we will continue to monitor the situation to determine whether further action is required.

Cross-agency issues

Legal processes involving the movement of people and goods across the border are complex and involve multiple government agencies. Staff of the Ombudsman’s office visited Christmas Island this year, where Commonwealth Government agencies involved in the interception, transfer and processing of asylum seekers include Customs and Border Protection and the multi-agency authority Border Protection Command (comprising officers from both Customs and Border Protection and the Department of Defence), the Department of Immigration and Citizenship and the Australian Federal Police.

A complaint to our office highlighted the impact of this complexity on the simple receipting of property. A complainant’s wallet, which it is alleged had contained currency, was handled by officers from a number of agencies at various levels of responsibility before the complainant realised the money was missing. This multiple handling made it difficult to ascertain what had happened to the wallet.

Cross-agency issues also arise at airports, where the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service, the Australian Federal Police, and Customs and Border Protection all operate. Similar issues occur with the processing of inbound international mail, where Australia Post and Customs and Border Protection functions cross over.

Feedback from agencies indicates that they have taken steps to ensure people understand what each agency is responsible for. It is critical that the public understand how to make complaints about Government services, including in multi-agency environments.

Update from last year

In the 2009–10 annual report we referred to our own motion report (see previous section), which has now been released and the recommendations largely implemented.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

This year we engaged in numerous liaison activities, for example with Border Protection Command regarding its role in the interception and transfer of asylum seekers on Christmas Island. Recent liaison activities have concerned the new airport screening processes relating to internal examination of travellers suspected of internally concealing prohibited substances. We have developed our role as a resource for Customs and Border Protection in the introduction of new processes to support change in the airport environment, and presented to the Enforcement & Investigations Division on our role.

Looking ahead

Passenger screening will be a priority for our office in the year ahead. In particular we will liaise with Customs and Border Protection regarding the trial of new screening technology and the development of related policies and procedures. We will monitor passenger complaints and broader feedback on this topic and assess the need for further scrutiny by our office as 2011–12 progresses.

We will be monitoring the way that Customs and Border Protection deals with and responds to complaints, and assess the need for further action in this area. A priority will be whether responses to complaints are appropriate, in terms of the remedies offered, level of explanation provided and plain language expression used.

We will continue to:

- investigate individual complaints

- raise complaint issues with Customs and Border Protection to ensure that information can be used as impetus improving their administration

- be a resource for Customs and Border Protection on good administrative practice as they develop new policies and procedures.

Centrelink

Overview

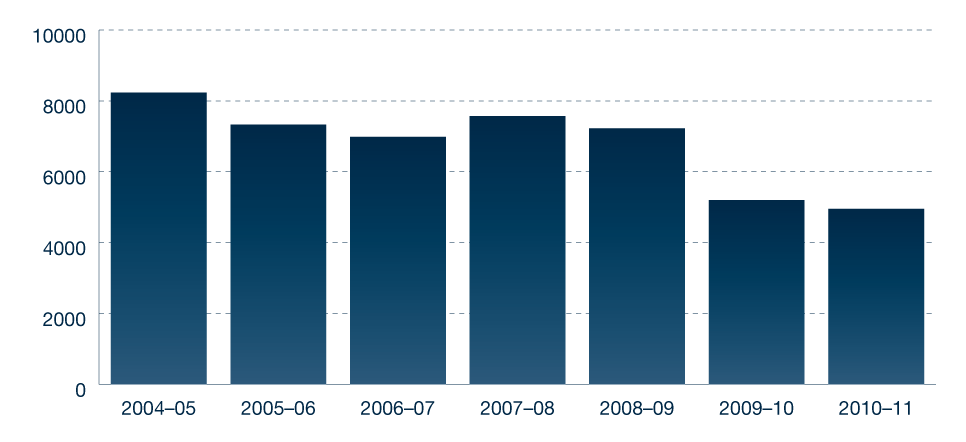

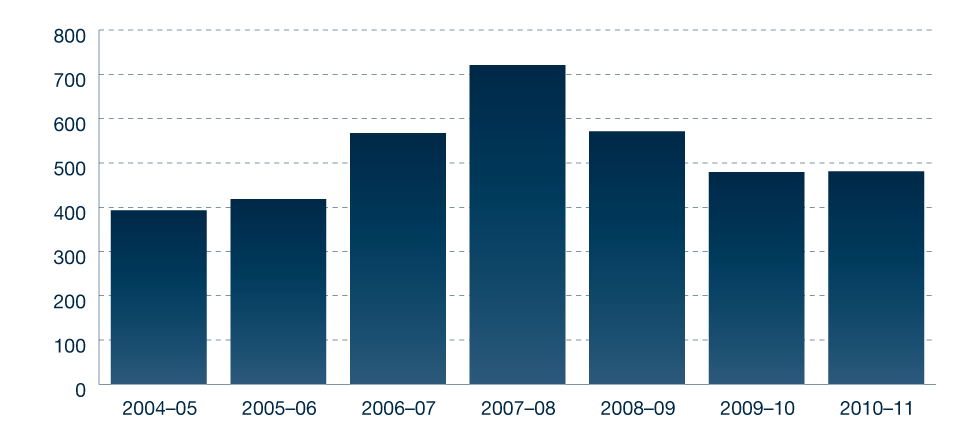

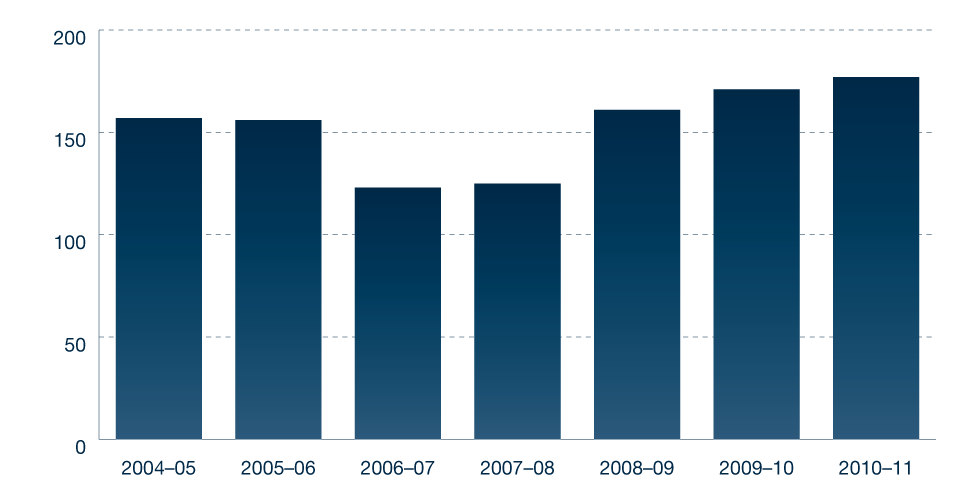

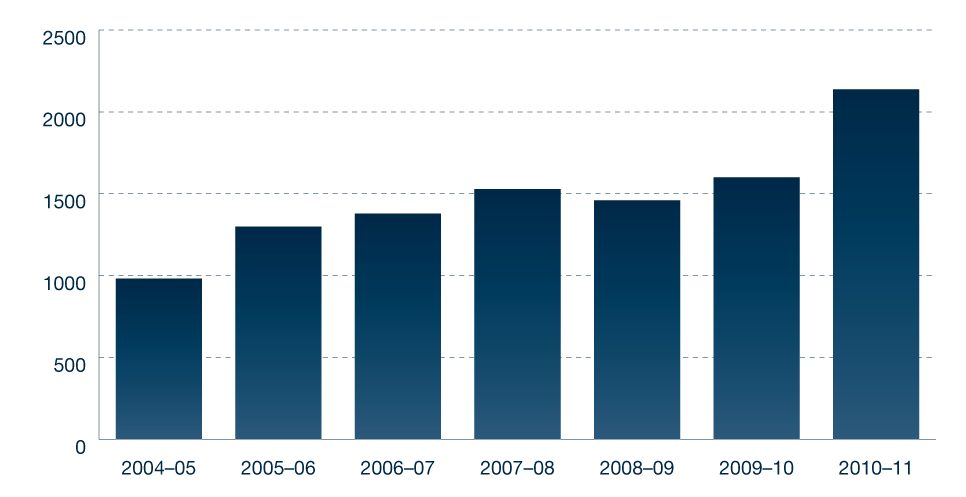

In 2010–11 the Ombudsman’s office received 4954 approaches and complaints about Centrelink compared to 5199 in 2009–10. This represents a 4.7% decrease over the previous year and is the lowest number in 11 years. The figure also includes 50 approaches relating to ‘Closing the Gap in the Northern Territory’ initiatives. Centrelink remains the agency about which the Ombudsman receives the highest number of complaints. This outcome is not unexpected given the volume, complexity and diversity of Centrelink’s workload. Figure 5.3 shows the trend in approaches and complaints over the past seven years.

During 2010–11 the office investigated 1098, or approximately 22.4%, of the 4910 approaches closed during the period. Consistent with previous years, the payments most commonly complained about in 2010–11 were Disability Support Pension, Newstart Allowance, Age Pension, Family Tax Benefit and Youth Allowance. The most common complaint reasons were problems with claims for payment, debt raising and recovery, delays, and suspension or cancellation of payments.

Centrelink’s programs impact upon some of the most vulnerable members of the Australian community, so the need for Centrelink to be accessible, transparent and accountable in the delivery of payments and services has been a particular focus for the Ombudsman this year. The case study below provides an example of the types of difficulties vulnerable customers can experience and how greater flexibility on the part of Centrelink can ensure a better outcome.

Figure 5.3: Centrelink approach and complaint trends 2004–5 to 2010–11

Debt raising

We received a complaint from Mrs A on behalf of her son Mr A, that Centrelink had raised a debt against him for overpayment of Youth Allowance. Mrs A told us that Mr A had a medical condition which made it difficult for him to communicate with Centrelink without assistance. She said that the condition had prevented Mr A from continuing with his studies and had resulted in the debt being raised against him. Mrs A stated she had contacted Centrelink when Mr A ceased studying but Centrelink did not cancel his Youth Allowance.

We asked Centrelink to reconsider the decision to raise the debt and asked the Authorised Review Officer to consider if all or part of the debt could be waived in special circumstances. We highlighted Mr A’s likely eligibility for another payment instead of Youth Allowance during the debt period, his lack of awareness of the overpayment, the difficulties he had managing his affairs and Centrelink’s error in failing to cancel the Youth Allowance payment. The Authorised Review Officer acted quickly to waive recovery of the debt in full and initiated a compensation claim under the Compensation for Detriment caused by Deficient Administration scheme for a possible underpayment of a more favourable benefit.

Complaint themes

Quality of advice

The Ombudsman’s office has received many complaints from members of the public who complain that Centrelink has not provided them with correct and complete advice about their possible entitlement to social security programs and payments.

The social security program is complex and in navigating the system, members of the public rely on Centrelink staff to provide accurate and timely advice about their entitlements to social security at various times of life. The following case study highlights the importance of staff awareness and training about the social security system as well as the consequences of not providing a customer with complete advice about their entitlements.

Providing complex information to customers

Mr B complained to this office that his wife, Mrs B, had not been informed of the pension bonus scheme (PBS) when she asked Centrelink for information about the age pension in 2004. As a result, Mrs B claimed the age pension and between 2004 and 2007 received less than she would have if she had registered for the Pension Bonus Scheme. Centrelink then declined to pay compensation to Mrs B under the Compensation for Detriment caused by Deficient Administration (CDDA) scheme. This office investigated and identified that Mrs B had been incorrectly permitted to lodge an abridged version of the Age Pension claim form, which did not include information about the Pension Bonus Scheme. We recommended to Centrelink that the CDDA decision be reconsidered as proper procedures had not been followed. The CDDA reconsideration resulted in compensation being paid to Mrs B.

System issues

Over the years, the Ombudsman’s office has received complaints that involve ‘computer system errors’ and/ or ‘technical glitches’ that have impacted on a customer’s payment. The complaints have demonstrated the frustration and delays customers experience in having such problems rectified. In some cases, the Ombudsman’s office has observed that Centrelink has put in place manual work-arounds until system reforms can be carried out. This can result in the potential for error, accidents and omissions which can be difficult for both Centrelink and the customer to identify.

Computer system errors

Mrs C approached this office as her husband, Mr C, was having difficulty reporting his fortnightly employment income to Centrelink in relation to his Newstart allowance and Mrs C’s Age Pension. Centrelink required Mr C to contact them by telephone or in person to report even though his preferred method of reporting was online. Due to a systems problem, the calculation of the Age Pension rate paid to Mrs C to reflect the work bonus rules needed to be done manually by a Centrelink officer. Following investigation by this office Centrelink implemented a manual system in which two Centrelink officers were notified by reminder email to manually process the income information each fortnight and Mr C was able to resume reporting the information online. We remained concerned that this arrangement was open to human error and that other Centrelink customers may be in a similar situation.

Following further investigation we were informed by Centrelink that the problem arose from an error in its pension computer system. Centrelink identified approximately 1,800 affected customers and, in May 2011, it identified that around 800 had been underpaid. In June 2011 Centrelink implemented a system fix and paid arrears to approximately 800 customers whose entitlements had been under-paid.

Internal Centrelink reviews

Complaints about Centrelink review processes are regularly received by the office. As discussed below, an own motion investigation and report was released on this issue earlier this year and Centrelink is trialling a new internal review framework which aims to address some of the issues raised in the report such as timely access to review.

Debt raising and recovery

Debt has continued to be a common issue of complaint to our office in 2010–11. In particular, we have received a number of complaints from customers who believe that Centrelink has raised a debt against them on the basis of incorrect information and without giving them an opportunity to correct the information. We have also received many complaints about Centrelink’s debt recovery methods, including automatic referrals to private collection agents and initiation of garnishees1 and legal action even while a repayment arrangement is being adhered to. These issues may be explored in more detail in 2011–12.

Systemic issues

Systemic issues this year included the following matters:

Australian Government Disaster Recovery Payment

Earlier this year, the Australian Government activated the Australian Government Disaster Recovery Payment (AGDRP) in relation to the Queensland, New South Wales, Victorian and Western Australian floods, Cyclone Yasi and Western Australia fires. This resulted in an increase in AGDRP applications to Centrelink and a modest increase in complaints to this office about Centrelink in the three months following the disasters. In the main, we were able to refer complainants back to Centrelink to obtain information about seeking review of a decision to refuse a claim for the AGDRP.

Our office also received a number of complaints about delays in processing AGDRP claims for Cyclone Yasi, which Centrelink advised us occurred as a result of the need for it to seek policy clarification from the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), as the policy department, about one of the eligibility criteria. We intend to discuss these delays with the department shortly, and will also be seeking further information from it about the AGDRP policy as it relates to claims from ‘non principal carers’ who had a child in their care at the time of the disaster.

Implementation of tribunal decisions

The Ombudsman’s office continues to have concerns about Centrelink’s processes for scrutinising and responding to tribunal decisions that have broader implications for the policies and procedures as instructed by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) and the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR).

This issue arose in the Ombudsman’s report Review rights for Income Managed people in the Northern Territory (10|2010) where our investigation of a complaint identified a Social Security Appeals Tribunal decision on the Tribunal’s lack of jurisdiction to consider reviews about Income Management exemptions. The Tribunal’s decision went unnoticed by FaHCSIA and Centrelink, but should have prompted the two agencies to assess the decision and consider the need for appeal, legislative amendment or a change to administrative processes. The specific issue of this report became redundant when the new Income Management arrangements were rolled out in mid-2010, but we are continuing to follow up on the broader issue of timely analysis and action in response to significant Tribunal decisions.

The Ombudsman’s office has observed other complaints where the Administrative Appeals Tribunal has made decisions that impact upon the interpretation and administration of social security law and have implications for other customers. However, Centrelink and the policy departments do not always appear to have responded promptly to clarify policy guidelines, creating an ongoing inconsistency between how Centrelink and the tribunal interpret the law. Our office is currently pursuing with Centrelink, FaHCSIA and DEEWR the decision-making processes around the review of tribunal decisions, particularly where they relate to key definitions in the law.

Customers in crisis

In recent years the Ombudsman’s office has received complaints from people in crisis who have been advised by Centrelink that they are not eligible for financial assistance. In many of these complaints the advice provided by Centrelink has been correct and the customers do not meet the legislative or policy requirements to receive a crisis, urgent or advance payment. However, our investigation of these complaints has led us to query whether the current arrangements for providing crisis or emergency payments are too narrow and unreasonably prevent some needy customers from accessing support. Some of these issues were raised in our submission to the Australian Law Reform Commission’s inquiry into the treatment of family violence in Commonwealth laws. This issue may be further explored in 2011–12.

Cross-agency issues

Many complaints to the Ombudsman require us to make enquiries of more than one agency. This is often the case where one agency is responsible for delivering a product or service, while another has responsibility for the relevant policy or law. As the largest government service delivery agency and portal for a variety of government payments and services, this is often a factor in Centrelink complaints.

Child care payments – Centrelink and DEEWR

The intersection between Centrelink and the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) in the delivery of child care payments has been a source of complaints to our office over a number of years. In August 2010, a ‘contact once’ model was implemented to simplify complaint handling about child care issues by placing a responsibility on the agency with which the customer makes contact to liaise with the other agency to resolve the problem and provide a response directly to the customer. Although this has improved the resolution of complaints between Centrelink and DEEWR some problems still remain as highlighted in the example below.

Reasonable maintenance action data transfer – Centrelink and CSA

Over the past twelve months our office has been working with Centrelink and the CSA to investigate their respective roles in administering the ‘reasonable maintenance action test’ for Family Tax Benefit. Specifically, we have been trying to find out why some customers have incurred substantial Family Tax Benefit debts as a result of Centrelink finding out some years later, via an electronic data transfer from the CSA, that the customer has not had a child in their care for a period. Centrelink’s processes rely upon the transfer of computer data as the basis for making a complex decision about whether a person has taken reasonable maintenance action. We do not consider that this is an appropriate use of computer-assisted decision making.

This is also discussed in the Child Support Agency overview on page 55, and will continue to be an area of focus for our office over the coming year.

Cross-agency issues

In November 2010 Mr D claimed Child Care Benefit to enable him to receive Child Care Rebate through Centrelink in relation to his son’s child care attendance. Centrelink told Mr D that due to a computer system problem his child care provider had been unable to submit child care usage details via the DEEWR Child Care Management System, which in turn prevented payment of the rebate by Centrelink. Mr D complained to this office after making numerous complaints to Centrelink.

This office investigated the complaint with Centrelink and DEEWR. Centrelink provided us with email correspondence between itself and DEEWR which indicated DEEWR was not responding to Centrelink about the issue. DEEWR advised this office that it had made an error in trying to obtain child care attendance figures from the wrong child care provider and had also attempted to apply approval for the incorrect dates. As a result DEEWR was able to correct the errors and Centrelink paid Mr D Child Care Rebate in April 2011.

We are continuing to follow up with Centrelink and DEEWR to ensure customer complaints that involve multiple government agencies are able to be easily resolved.

Reports released

The Ombudsman released the following reports in 2010–11 relating to Centrelink:

- The report Falling through the cracks—Centrelink, DEEWR and FaHCSIA: Engaging with customers with a mental illness in the social security system (Report 13|2010) was published in October 2010. Centrelink was one of three agencies investigated regarding service delivery to customers suffering from a mental illness. The report made a range of recommendations designed to improve engagement with, and services to, customers with mental health issues and disabilities. Subsequent to the report Centrelink has established an Interagency Working Group, comprising representatives of Centrelink, the Department of Human Services, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) and Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs to progress the Ombudsman’s recommendations, particularly in relation to training needs and updating policy guidelines. Centrelink has also convened a Working Party consisting of agency representatives and a number of welfare, disability, advocacy and carer organisations to guide implementation of the more complex recommendations. Our office will continue to monitor implementation of the report recommendations. DEEWR has also provided an update on the implementation of the recommendations relevant to its areas of policy responsibility including Job Services Australia providers. Information about DEEWR’s progress in implementing the recommendations can be found at page 64 of the DEEWR chapter.

- The report Centrelink: Right to review–having choices, making choices (Report 04|2011) investigated Centrelink’s internal review processes and was published in March 2011. The report highlighted problems with the existing review processes and made a number of recommendations including that Centrelink improve the timeliness of reviews, limit the negative consequences of incorrect decisions pending review, improve the quality of original decisions and work with relevant policy departments to ensure that legislation and policy guides align to support improvements to the review system. Centrelink accepted the recommendations and advised that it had commenced a trial of an enhanced internal review process. The Ombudsman’s office accepted Centrelink’s offer to provide input to the design and review of the new framework and meets regularly with Centrelink. We expect to release a follow-up report on the progress of the report recommendations once the new framework has been implemented.

- Centrelink was one of two agencies investigated as a result of a complaint about the Income Management regime in the Northern Territory. The report Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and Centrelink: Review rights for Income managed people in the Northern Territory (Report 10|2010) was published in August 2010 highlighting significant failure in the provision of review rights to people affected by the former income management regime. Further information is included in the Indigenous overview on page 87.

- Centrelink was also included in a report titled Talking in Language: Indigenous language interpreters and government communication (Report 05|2011), published in April 2011. Centrelink was responsive to this report and participated in a workshop with the other agencies included in the report to discuss implementation of the recommendations. Further information is included in the Indigenous overview on page 87.

- Submissions were made to the Australian Law Reform Commission’s inquiry into the treatment of family violence in Commonwealth laws, regarding Issues papers 38 (child support and family payments) and 39 (social security). Staff from the Ombudsman’s office also participated in the Commission’s expert roundtable to discuss proposals regarding social security law.

Update from last year

Transfer to age pension

In our last annual report, we discussed a complaint that highlighted a systemic problem with the way that some customers were transferred to Age Pension when they reached Age Pension age. At that time we had sought information from Centrelink about its processes for assessing the claims of affected customers and determining whether they were entitled to backdated payments. We have since been advised that the 1,800 affected customers were contacted by Centrelink and, where appropriate, arrears of Age Pension were paid to the date they first became eligible for an increased rate of payment.

Review of circumstances leading to a fraud conviction

In May 2010 the Ombudsman’s office released an investigation report into the handling of a fraud matter by Centrelink and the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions. That report recommended that both agencies revisit their handling of the case and provide advice to the customer about appealing the recorded fraud conviction. In 2010–11 our office was advised that, following an appeal by the customer, the conviction was set aside and a verdict of acquittal recorded. The Director also provided an assurance to the customer that it did not intend to further pursue the matter.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

The office has increased its outreach and community engagement in an effort to be more accessible and to gain a better understanding of the issues faced by the people in the community. Community roundtables focused on social welfare issues were conducted with non-government organisations in capital cities last year. More recently roundtables have been held in Brisbane, Canberra and Melbourne.

Further information about the office’s involvement in stakeholder engagement and outreach can be found in Chapter 7— Engagement .

Looking ahead

Department of Human Services – Service Delivery Reform

As the Department of Human Services continues to progress its Service Delivery Reform agenda, our office will be closely observing the impact of any changes on Centrelink customers. We are particularly interested in the issues of accessibility, information sharing and the standardisation of procedures and policies across the portfolio. We will be seeking regular updates on the work in these areas, and will participate in working groups and consultative forums where appropriate.

Changes to payments and services

The 2011–12 Federal Budget flagged a number of substantial changes to some payments and services delivered by Centrelink. Of particular interest to our office are the changes to eligibility requirements for Disability Support Pension, and the rolling out of Income Management and increased compliance activity initiatives in target areas. We will continue to seek updates from Centrelink as it implements these reforms, and highlight relevant issues of concern that may arise from complaints to our office.

Debt raising and recovery

Over a number of years the Ombudsman has received complaints about Centrelink’s practices in raising and recovery of social security and family assistance debts.

As mentioned in the ‘Complaint Themes’ section, particular areas of focus have included procedural fairness in decision making, the quality of information provided to customers about the reasons for a debt, and the willingness of staff to adapt debt recovery arrangements to the customer’s circumstances.

This will be a continued area of attention in the coming year.

Income management decision making

Our office is currently conducting an audit of Centrelink’s decisions to apply Income Management (IM) to a person because they are assessed as being a Vulnerable Welfare Payment Recipient, and its decisions not to exempt a person because Centrelink has determined there are indicators of Financial Vulnerability. The Ombudsman will release a public report in 2011–12 regarding the results of this audit.

Child Support Agency

Overview

The Child Support Agency (the Agency) is part of the Commonwealth Department of Human Services1, and is responsible for the assessment and transfer of child support payments between separated parents.

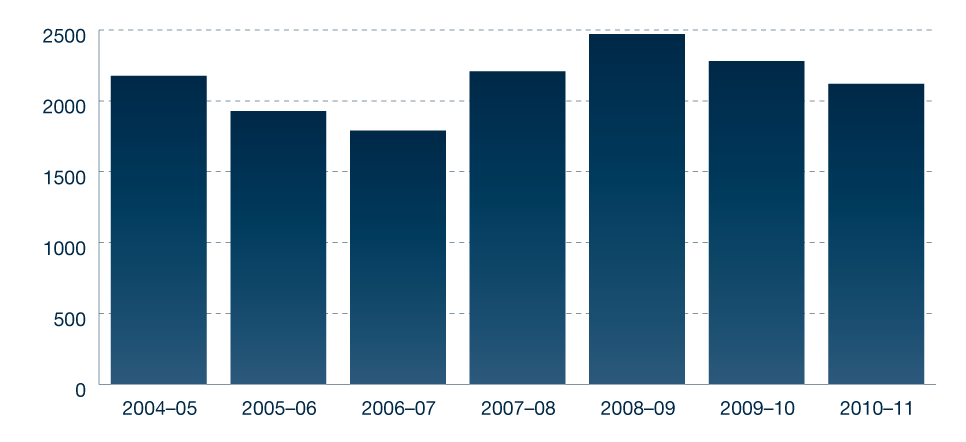

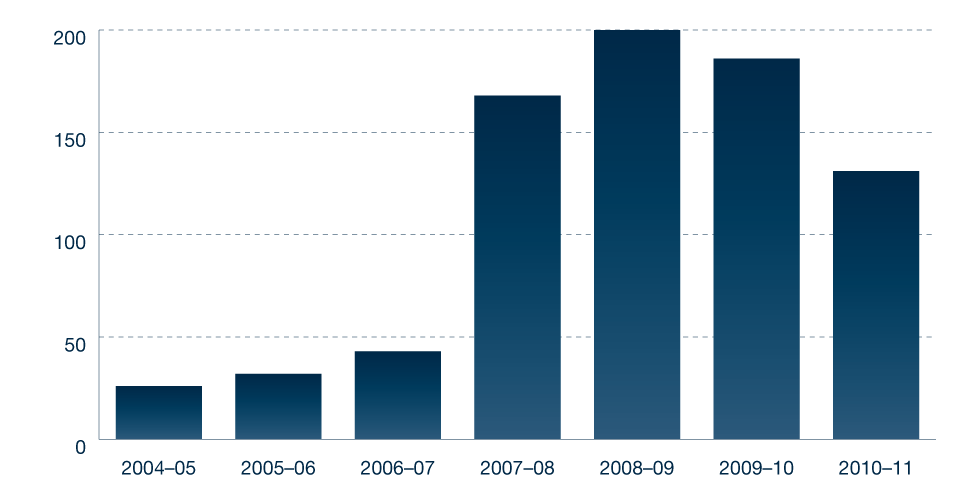

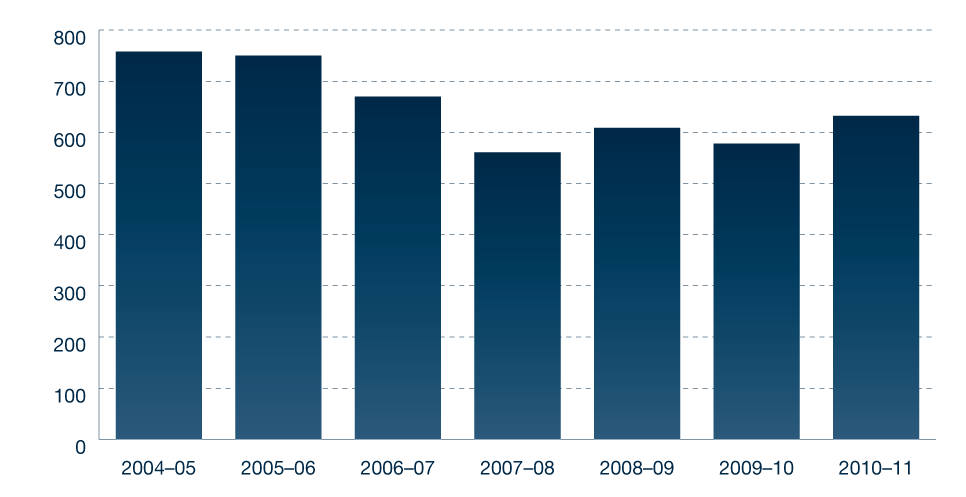

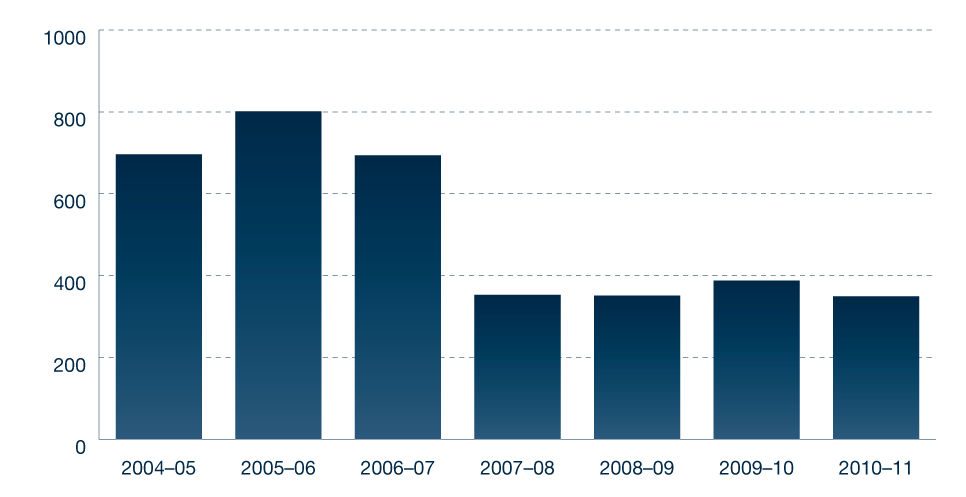

Complaints about the Agency still make up a considerable proportion of the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s workload. However, the actual number of complaints received by our office has dropped slightly (2,121 complaints in 2010–11 compared to 2,280 in 2009–10). This continues a downward trend since 2008–09, when we received 2,471 complaints about the Agency – a ‘spike’ largely attributable to the Agency’s implementation of a new child support formula. Interestingly, the Agency also fell from third to fifth most complained about agency in 2010–11, although this is attributable to more complaints about other Commonwealth agencies, rather than fewer complaints about the Agency.

We investigated approximately 28% of the complaints that we finalised in 2010–11. The other 72% either raised issues that we considered did not warrant investigation, or which the complainant could readily or more appropriately pursue through other avenues. Those other avenues include using the Agency’s internal complaints or objection process; appealing to the Social Security Appeals Tribunal; or applying to a court. Whenever we decline to investigate a person’s complaint about the Agency, we explain our reasons for doing so, and provide information about the other ways the person can address their complaint issue. We also record information about the issues raised by each complaint to assist us in monitoring trends in the Agency’s administration.

There have been some significant policy and service delivery changes affecting the Agency this year. As we discuss below, those changes have generally improved aspects of the Child Support Scheme, but there have been some teething problems.

Figure 5.4: Child Support Agency approach and complaint trends 2004–5 to 2010–11

Complaint themes

Which Child Support Agency customers complain to the Ombudsman?

The Agency’s customers fall into two quite distinct groups: people (usually parents) who are entitled to receive child support payments (‘payees’); and those parents who are liable to pay child support (‘payers’). From 1 July 2010, we started recording whether our complainants were payees or payers. We hoped this data would help us to better analyse the underlying causes of Agency complaints. In 2010–11, slightly more than two-thirds of the people who complained to us about the Agency were payers. At this stage we do not possess data to indicate the reasons for this discrepancy so it is not clear to us whether this means that payers are generally less satisfied with the Agency’s administration than payees. We will however be doing more to ensure that all Agency customers are aware of the Ombudsman’s services and their right to complain to us if they are dissatisfied with the Agency’s administration.

Right to know

Mr E is entitled to receive child support from his former wife, Ms F. Mr E complained to us about the Agency’s failure to keep him informed of its attempts to collect arrears of child support from Ms F. However, Ms F had recently left her job and this had made it more difficult for the Agency to collect child support. Mr E told the Agency that Ms F intended travelling overseas in the near future and had asked it to consider making a Departure Prohibition Order (DPO) to prevent her leaving Australia without paying her child support debt. The Agency refused to tell him whether it had done so.

When we contacted the Agency office administering Mr E’s case, it advised us that the Privacy Act 1988 prevented it from telling Mr E any personal information about Ms F. The Agency believed that this meant that it could not tell Mr E whether it had issued a DPO against Ms F. We wrote to the Agency’s national office and expressed our view that Parliament actually included a specific provision in the child support legislation to allow the Agency to provide reports to a payee about collection actions, and this meant that the Agency could disclose limited amounts of personal information to keep the payee informed. The Agency agreed, clarified the position for its staff and apologised to Mr E.

Debt enforcement

A perennial issue in complaints from Agency payees is that they are unhappy with the Agency’s action to collect child support from the payer. These complainants frequently also say that the Agency has failed to provide any meaningful report about the efforts that it has made, or will make in the future. Often the Agency will tell the payee that it is not allowed to provide this sort of information to them because it would breach the payer’s privacy. However, as the following case study shows, this is not strictly true. We believe the Agency needs to recognise that it is important to be accountable to the payee for the actions that it takes in its efforts to collect child support for them.

We have also advised the Agency of our concern that its usual procedures for gathering information to assist it to collect child support do not currently include requiring the debtor to attend an interview to answer questions about their finances. We consider including an interview would be a cost effective measure that would complement the other inquiries that the Agency makes via third parties, particularly in cases where the debtor’s lifestyle is not consistent with his or her known income or assets.

Overseas cases

The Agency can make (or continue) a child support assessment in a case where the payer or payee lives overseas. It can also register and collect spousal or child maintenance payable under a court order or administrative assessment made in a `reciprocating jurisdiction’. We have noticed, however, that the Agency’s administration of some of these cases can be hampered by a failure to set reasonable customer expectations, communication problems, delays, or general lack of responsiveness. The following case study illustrates all of these themes.

So far away

Mrs G lives in the UK, where she obtained a court order for child and spousal maintenance from Mr H, who lives in Australia. The UK authorities sent the order to the Agency in Australia for registration and collection. Mrs G complained to us that the Agency had only registered the child maintenance component of the order. Mrs G sent the Agency a series of emails about this problem over a six month period, but the Agency had not responded to many of them. She felt the Agency was ignoring her and she had no faith that it would address her concerns.

When we contacted the Agency we found that it was confused about the wording of Mrs G’s order. It had acted promptly to register the part of the order about child maintenance, but although it could legally collect spousal maintenance, it did not understand the wording of the order about the period over which those payments were to be made. The Agency had written to the UK authorities for clarification, but it had not received a response, or followed this up. The Agency also advised us that it may have made a mistake when it worked out how much child maintenance Mr H had to pay under the order. The Agency had also not answered Mr H’s queries about his debt to the Agency, which he disputed.

We persuaded the Agency to deal with all of Mrs G and Mr H’s concerns as objections to the details entered into the child support register. This meant that a single Agency officer reconsidered all the information, made a decision about the correct amounts of child and spousal maintenance payable under the UK order, amended the Agency’s records accordingly and provided written decisions to Mr H and Mrs G. This resolved the impasse and gave them the option of appealing to the Social Security Appeals Tribunal if they disagree with the Agency’s decisions.

Systemic issues

Garnishee notices to collect child support debts

The Agency can serve an administrative garnishee notice upon a person who holds, or is likely to hold in the future, money on account of a child support debtor2. A person who fails to comply with the notice may be subject to penalties, which might include being required to pay the debt out of their own funds. This can be a very effective way for the Agency to collect child support from a reluctant payer. However, it is important that the Agency monitor whether the third party actually complies with the notice.

My boss stole my money!

Mr J complained to us that the Agency was chasing him to pay around $8,000 in child support arrears. He said he had paid off this debt years ago, through deductions from his contract payments. Mr J said the Agency should get the money from Mr J’s former employer, who had gone into liquidation.

We investigated Mr J’s complaint and found that the Agency instructed Mr J’s employer to deduct 30% from every payment they made to Mr J, and send that money to the Agency. The employer made the deductions, but failed to transfer all the money to the Agency. When the Agency’s efforts to encourage the employer to comply did not succeed, it failed to refer the employer’s case for prosecution. Even more worryingly, it decided to leave the arrangement in place, so more deductions were made from Mr J’s payments. When the Agency learned that the employer had gone into liquidation, it told Mr J that this was now a matter between Mr J and his former employer.

During our investigation, the Agency accepted that it had failed to take decisive and appropriate action in Mr J’s case and that this had caused Mr J to lose a substantial sum of money. It offered Mr J compensation equivalent to the sum that his employer had retained. The Agency proposed to Mr J that it would apply that compensation to his child support debt, and that this money would then be transferred to his former partner for the support of their children.

The Agency has advised us that it is planning a range of procedural and computer system improvements, plus staff training, to address the systemic problems exposed by Mr J’s complaint. It is also in discussion with its policy department (of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs) about the possibility of legislative changes to ensure that the Commonwealth, rather than Agency customers, bear the financial risk in cases like Mr J’s.

In another case, the Agency failed to withdraw a garnishee notice after the person’s child support debt had been paid off. The officers who refunded the overpaid money to the payer failed to make sure that the employer was instructed not to make further deductions, so they continued to deduct and send money to the Agency. We intend working with the Agency in the coming year to highlight areas where it can improve its administration of garnishee notices.

Child Support Overpayments

We have received a small but steady stream of complaints from both payers and payees since at least 2007 about the Agency’s approach to overpaid child support. The payees’ issues include the Agency’s failure to clearly explain the reason for the overpayment and how it was calculated, the perceived unfairness of requiring them to repay a debt received in good faith, that their child support payments were stopped without warning when the Agency decided they had been overpaid, and the Agency’s refusal to allow them to repay the overpayment by withholdings from future child support payments. The payer complaint issues include the Agency’s refusal to refund the overpaid amount until it has been recovered from the payee, to recover it fast enough, or its failure to recover the overpayment at all.

We acknowledge that child support overpayments are a difficult problem, requiring the Agency to carefully balance the interests of both parents, the children and the Commonwealth. The Agency has advised us that it is well advanced in developing a new approach to recovering overpayments. It has undertaken to provide us with a briefing about that new approach in advance of implementing it. We will be carefully monitoring complaints about child support overpayments in future to see whether the new approach is an improvement.

Cross-agency issues

The Agency needs to work closely with a range of other Commonwealth agencies to administer the Child Support Scheme. Most notably, the Agency routinely has interactions with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and Centrelink, as set out below, the Agency:

- relies upon the ATO for details of parents’ incomes

- instructs the ATO to deduct child support payments from debtors’ tax refunds

- and Centrelink exchange information about the proportion of time that children spend in each parent’s care, for the purposes of working out child support and family tax benefit entitlements

- tells Centrelink whether a person has applied for a child support assessment, so Centrelink can work out that person’s family tax benefit entitlement

- instructs Centrelink to deduct child support payments from benefits paid to Centrelink customers, and Centrelink transfers those payments to the Agency, which in turn pays them to the payee.

Many of these interactions are automated, but problems with those automated processes can prove difficult to resolve.

Centrelink / Child Support Agency

We have also been working closely with Centrelink and the Agency for more than a year on a project about their interaction to administer the ‘reasonable maintenance action test’ for family tax benefit. We have been trying to find out the underlying reasons for certain mutual customers acquiring large family tax benefit debts when Centrelink belatedly discovers that the Agency has not for some time had a current child support case for one of the children in their care.

Social Security Appeals Tribunal/Child Support Agency

The Agency also needs to work with the Social Security Appeals Tribunal (the Tribunal), which has jurisdiction to review the Agency’s objection decisions. The Agency is responsible for copying and sending the relevant documents from its file to the Tribunal and to the parties to a review. The Agency must also implement the Tribunal’s decision if the Tribunal changes the Agency’s decision.

We have received two complaints alleging an error in the Agency’s implementation of the Tribunal’s decision, or alternatively an error in the Tribunal’s decision. We have had some success in resolving these complaints by investigating them with the Agency. However, we decided that it would not be efficient to contact the Tribunal to seek to clarify the intended effect of its decisions, because of the difficulties we experienced in investigating another unrelated complaint.

The Principal Member of the Tribunal has discontinued her predecessor’s arrangements which allowed us to contact the relevant Tribunal registry to clarify a complaint, or conduct simple investigations. She has also asserted that the Ombudsman has no power to investigate decisions made by Tribunal Members in relation to a review. This is something we will seek to resolve in the future through continued contact with the Tribunal and seeking the advice of the responsible policy Department, about the intent of the relevant legislation.

Reports or submissions released

The Ombudsman made the following reports and submissions about the Agency in 2010–11:

- Report 11|2010 — Child Support Agency, Department of Human Services: Investigation of a parent’s ‘capacity to pay’ , published August 2010. The Agency responded positively to the report and we are monitoring its implementation of the recommendations.

- Report 14|2010 — Department of Human Services, Child Support Agency: Unreasonable Customer Conduct and ‘Write Only’ policy , published November 2010. The Agency has developed new procedures in the light of this report and it has reviewed all of the cases where it had previously restricted customers to ‘write only’. In the coming year we will be examining the Agency’s records of those reviews and providing feedback on the Agency’s new policy and procedures for managing unreasonable customer conduct.

- Submission to the Australian Law Reform Commission’s inquiry into the treatment of family violence in Commonwealth laws, Issues papers 38 (child support and family payments) and 39 (social security). Staff from the Ombudsman’s office participated in the ALRC’s expert roundtable to discuss proposals regarding child support and family assistance.

Update from last year

In our 2009–10 report we mentioned changes to the child support legislation that would commence from 1 July 2010 about ‘care percentage’ decisions and income estimates.

The amended legislation about ‘care percentage’ decisions was part of a broader service delivery reform that aligned the rules applied by the Child Support Agency and Centrelink for working out a care percentage, and enables either agency to make a decision that applies across both agencies. Centrelink and the Agency have provided us with regular briefings about the implementation of the alignment of care initiative. We have investigated a small number of complaints about delays or failures in the automated transfer of care percentage data between the two agencies. We will continue to monitor this issue.

In 2010–11 we have not seen any increase in complaints about the Agency’s administration of income estimates under the new rules. At the same time, we are receiving fewer complaints about delays in the Agency’s reconciliation of old income estimates.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

We maintain a close working relationship with the Agency, meeting regularly with senior staff, and participating in a range of stakeholder groups and working parties convened by the Agency and its policy department FaHCSIA. These include: the Child Support National Stakeholder Engagement Group; various State Stakeholder Engagement Groups; and the NSW Legal Liaison Group. We keep in contact with many of the community groups involved in those meetings between sessions.

We participated in the Agency’s Domestic Violence working party, and an Agency stakeholder consultation on its project to simplify child support assessment notices; we provided feedback on the Agency’s proposed new account statements for payers; and we met with a consultant conducting a review of the Agency’s privacy practices.

We held successful community round table meetings in Sydney and Adelaide in late 2010 to talk about the Ombudsman’s work in relation to the Agency. We also gave a presentation at a conference of the NSW Women’s Refuge Movement about the assistance that the Ombudsman can provide to people having problems with Centrelink or the Agency regarding homelessness, family breakdown or family violence.

In June 2011, we conducted outreach to the Central Coast of New South Wales, where we had talks with the electorate staff of a Federal MP, a community legal centre specialising in domestic violence and a non-government agency that provides free meals, support and referrals to homeless people.

Our regular and open communication with stakeholders has enriched our understanding of the experiences of those who deal with the Agency and alerted us to issues that are not readily apparent from the complaints we receive. We have also been able to put some of our contacts in touch with each other so they can share information and strategies for dealing with child support matters.

DNA tests for single mothers

In late 2010, we attended a child support stakeholder meeting where a community legal centre staff member told us the centre was unable to get Legal Aid funding for DNA tests for single mothers wanting to claim child support. Not only did this mean that these women could not receive child support, they were also at risk of Centrelink deciding they were not ‘taking reasonable maintenance action’ and cutting their Family Tax Benefit payments. Knowing such funding is available in other States, we arranged for one of our contacts in a Legal Aid office (in a State that provides funding for the purpose) to contact the community legal centre. The centre has now secured Legal Aid funding for DNA tests.

Looking ahead

Although we encourage and in many cases expect Agency customers to use the Agency’s complaints service to resolve their problems, we are concerned that some people approach our office first, or do not wish to approach the Agency at all. We are also not confident that the people we advise to complain to the Agency first actually act on our advice. We intend developing a process, in consultation with the Agency, to directly transfer some complaints to its complaints service for resolution. This will occur only with the complainant’s consent. The person will be invited to come back to us if they remain dissatisfied with the Agency’s response.

In the coming year, the Agency’s customers will see further changes as the Department of Human Services reforms service delivery by integrating Centrelink, Medicare and Child Support into the one agency. We intend to monitor the Agency’s processes as it becomes part of the integrated department and will seek to influence and improve the service delivery model, particularly for vulnerable customers. We are especially keen to ensure that the Department of Human Services minimises the barriers to people using its complaints and internal and external review processes, reducing the need for them to approach the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

Comcare

Overview

In 2010–11 we received 64 approaches and complaints about Comcare, compared to 72 during 2009–10. Although this is not a significant change in the number of complaints received, it continues a downward trend in complaint numbers over the last three years.

Figure 5.5: Agency approach and complaint trends 2004–5 to 2010–11

Complaint themes

In 2010–11 we investigated 16 complaints, compared to 31 complaints in the previous period. Key complaint themes continue, as in previous years, to concern the rejection of claims for compensation, delays in the assessment of claims, and overall treatment of clients by Comcare and claim managers.

Comcare’s improved internal complaint-handling procedures may have assisted in reducing the number of complaints needing to be investigated by our office. Of note is that the number of remedies recorded by our office to ‘expedite action’ has halved, suggesting greater effort by Comcare to deal with timeliness issues.

Systemic issues

While the Ombudsman can investigate those complaints mentioned in the previous section, we cannot overturn individual decisions made by Comcare. If a complainant is unhappy with a decision, there is a formal two-tier review process available. The first step involves an internal Comcare review by someone not involved in the original decision. If still unhappy, the complainant can appeal to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

Although cases are often settled at the Administrative Appeals Tribunal pre-hearing, it can be a lengthy process to get to that point and some complainants question whether it is necessary for matters to have progressed that far before getting a more favourable decision.

Cross-agency issues

There were no significant issues identified.

Reports released

There were no reports issued this financial year.

Update from last year

As stated in last year’s annual report, Comcare provided an undertaking in response to Comcare and Department of Finance and Deregulation: Discretionary Payments of Compensation (Report 04/2010) that it would work to develop a compensation scheme similar to the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) scheme. Progress has been made. In June 2011 Comcare told this office that it is continuing its consultation with the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations and the Department of Finance and Deregulation in relation to the option of establishing a scheme, similar in nature to the CDDA scheme, within the Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1988 .

The recommendations of Report 04/2010 were considered by the Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee, which examined the lack of a proper compensation scheme for claimants who have been disadvantaged as a result of administrative errors by Government agencies not included under the CDDA Scheme. It recommended that the limit for payment in special circumstances provided for by the Public Service Act 1999 and the Parliamentary Service Act 1999 be increased from $100,000 to $250,000, thereby expanding an avenue for compensating some claimants affected by defective administration.

While we welcome the above recommendation, unfortunately it will not fully address the current inequities in compensation across different agency types. It is our position that people should have a mechanism to claim compensation where they have suffered a financial loss due to the defective actions or decisions of all agencies and contracted service providers that deliver services on behalf of the Australian Government. For this reason we welcome the Committee’s recommendation that Comcare, the Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations and the Department of Finance and Deregulation conclude their consultation in relation to creating a CDDA-type scheme, as a matter of priority. This will be a step towards achieving the goal of more equitable access to compensation across the whole of the public sector.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

Our office has developed an effective working relationship with Comcare that has assisted in the effective resolution of complaints. We generally meet quarterly with Comcare’s key contact area to discuss any issues arising out of complaints.

Looking ahead

In response to concerns by complainants about the review process we intend to work with Comcare to identify administrative changes that could be made to the review process that might improve claimant experience. With the assistance of Comcare, the initial step would involve monitoring the type and volume of pre-hearing settlements at the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. If this confirms the experience of complainants, steps will be taken to identify barriers to reaching the correct or preferable decision more quickly. This process would also involve working with the Tribunal.

The following case study is an example of how our office was able to assist complainants.

Delay in review

Ms M complained about the time taken by Comcare to complete a review of a decision that she requested in March 2010. Our investigation found that one of the requests for review had initially been overlooked. No action was taken to progress it until after we became involved.

Comcare finalised the review on 30 July 2010 and apologised to the complainant for the delay. Our office recorded administrative deficiency on the grounds of unreasonable delay, which Comcare accepted.

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

Overview

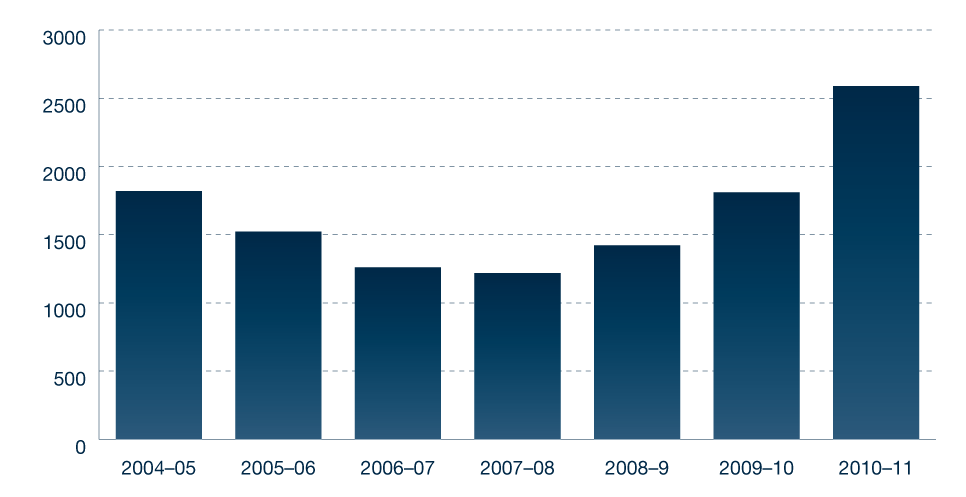

In 2010–11 we received 481 complaints about the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR, or the department), compared to 479 complaints in 2009–10 and 571 in 2008–09. The number of complaints investigated, as a proportion of complaints received, has reduced. This reflects the impact centralisation of DEEWR investigations by the office has had on complaints investigated. Such centralisation has enabled a greater level of specialisation and knowledge of the issues and thereby a greater capacity to assist complainants without having to undertake an investigation.

Figure 5.6: DEEWR approach and complaint trends 2004–5 to 2010–11

Complaint themes

The main issues raised with our office this year were in relation to:

- concerns about the department’s handling of complaints about Job Services Australia and Disability Employment Service providers

- issues relating to the Australian Apprenticeship Incentive Program

- the administration of child care assistance subsidies such as Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance.

There has been an overall reduction in the number of complaints about Trades Recognition Australia and the General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme since 2009–10. In relation to the reduction in complaints about Trades Recognition Australia, this is a trend that was noted in our last annual report and appears to be due to the implementation of the Job Ready Program in January 2010. That program provides greater clarity about the steps required by international graduates to demonstrate their job readiness before applying for permanent residency.

Systemic issues

The key systemic issues identified during 2010–11 were:

- adequacy of complaint handling by Job Services Australia and Disability Employment Service providers

- adequacy of record keeping by Job Services Australia and Disability Employment Service providers

- lack of advice about review rights where request to transfer to new Job Services Australia provider has been declined

- consistency and adequacy of decision making by Trades Recognition Australia

- adequacy of complaint handling in relation to child care assistance subsidies.

Cross-agency issues

The intersection between the department and Centrelink in the delivery of child care assistance programs such as Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance has been a source of complaints.

Please see the Overseas Students Ombudsman section on page 123 for information on the department’s role in that jurisdiction.

Reports released

Falling through the cracks

The report Falling through the cracks—Centrelink, DEEWR and FaHCSIA: Engaging with customers with a mental illness in the social security system (Report 13|2010) was published in October 2010. The report made a range of recommendations designed to improve engagement with and services to customers with mental health issues and disabilities. As the agency with responsibility for elements of social security policy and for Job Services Australia and Disability Employment Services providers, many of the recommendations required action on the part of DEEWR.

Subsequent to the report, DEEWR has participated in the Interagency Working Group, which was established to progress the Ombudsman’s recommendations, particularly in relation to training needs for Centrelink and Job Services Australia and Disability Employment Services staff and updating policy guidelines for payments and service delivery. Additionally, in the 2011–12 Budget, as a part of the National Mental Health Reform package, DEEWR secured $2.4 million in additional funding over the next five years to increase economic and social participation for people with mental illness.

Further information about Centrelink’s response to the report can be found at page 52 of the Centrelink overview.

Administration of the National School Chaplaincy Program

During 2010–11 our office conducted an own motion investigation into DEEWR’s administration of the National School Chaplaincy Program, in response to a report released by the Northern Territory (NT) Ombudsman following her office’s investigation of complaints about the program. The NT Ombudsman’s Report identified issues with the department’s administration of the Chaplaincy Program, which she was unable to investigate due to lack of jurisdiction. These matters were referred to our office for consideration, leading to the decision to initiate the investigation. On 26 July 2011 a report was published by our office, Administration of the National School Chaplaincy Program (Report No 06|2011). The department broadly agreed with the eight recommendations contained in the report.

The department has recently reviewed the Chaplaincy Program and the Government is currently considering the findings of that review. The department is currently reviewing its administrative arrangements, including the Program Guidelines, in preparation for the expansion of the program in 2012. We will be monitoring the action taken by the department in response to our recommendation in the year ahead.

Update from last year

Our office meets with the department quarterly to discuss systemic issues and to follow up on recommendations arising from formal reports and complaints where administrative deficiency has been recorded.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education activities

Our stakeholder engagement included:

- social support round tables

- regular briefings provided by the department regarding its programs

- involvement in a briefing regarding job services in Brisbane.

Looking ahead

Despite the implementation of the ‘Contact Once’ complaint model by the department and Centrelink in August 2010, the administration of child care assistance subsidies and complaint handling relating to those subsidies remains of concern to our office as complaints continue to be received. The identification of the cause(s) of problems with the administration of the subsidies, as well as the effectiveness of complaint handling in this area, will be the subject of further scrutiny by our office during 2011–12. This is likely to also involve engagement with Centrelink as the subsidies are jointly administered by the department and Centrelink.

Our office also intends to work further with the department to improve its complaint handling about Job Services Australia and Disability Employment Service providers, as this remains the main subject of complaints about the department.

Case studies

The following cases highlight good outcomes achieved through investigation and communication with agencies, on behalf of complainants.

Lost emails

Mr N complained to DEEWR by email about a Job Services Australia provider. He was dissatisfied that his complaint was dealt with by the provider rather than the department.

On investigation, the department advised that it had no record of the email complaint that Mr N had submitted, despite the provider having been notified by the department at the time that a complaint had been lodged. In response to our investigation the department conducted further searches and located Mr N’s email. The department advised that staffing changes and absences had resulted in the email being incorrectly classed as having been ‘actioned’.

The department apologised to Mr N for failing to respond to his complaint. It also took steps to try to prevent similar oversights from occurring in the future, including increasing staffing levels and implementing a strategy to manage risks associated with staff absences.

Following correct procedure

Mr O complained to the department about an incident that occurred at the office of his Job Services Australia provider in which the police were called to intervene. Mr O did not consider that the department had properly assessed his complaint.

Our investigation found that the department had conducted a thorough investigation of the incident and correctly referred Mr O to the relevant law enforcement authorities. However, the investigation also found that the provider failed to prepare an incident report about its decision to call the police, in accordance with the department’s procedures. Our office expressed concern about the provider’s failure to follow correct procedure. In response, the department advised it has taken steps to remind Job Services Australia providers of their obligations and the need to properly record and report incidents.

Improved communication

Ms P complained to our office about non-payment of Child Care Rebate for 2009–10. She advised that this had occurred despite advising her child care centre that her daughter had returned to her care. Despite attempts to resolve this issue directly with the child care centre, Centrelink and the department over a number of months, the payment issue was not resolved.

On investigation by our office it became apparent that Centrelink, the department and the child care centre needed to take further action to resolve Ms P’s complaint. In response to our investigation the department negotiated with the child care centre to facilitate resubmission of child care attendance information by the child care centre. This enabled the rebate to be paid to Ms P.

This case was a good example of the department working with a child care provider to achieve a reasonable outcome where each party (the parent and the provider) had different views on the matter and there had been no obvious error by any of the parties.

Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency and Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities

Overview

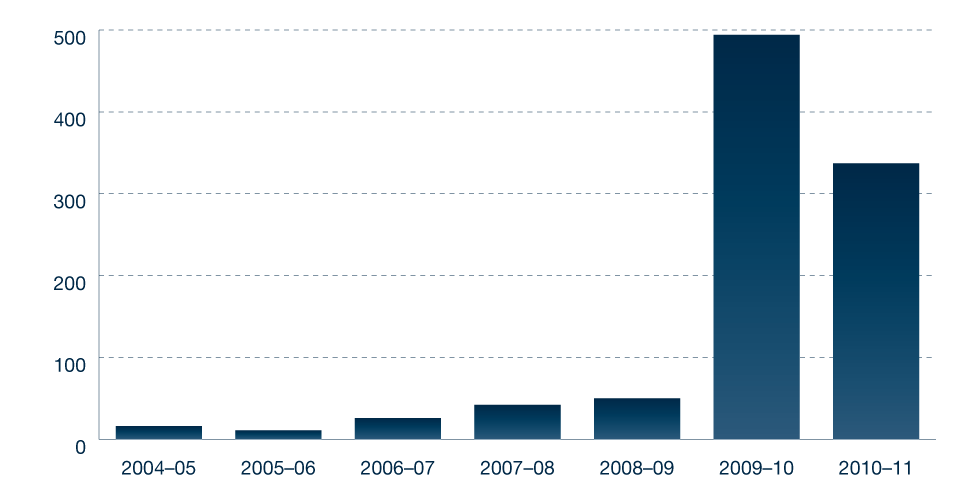

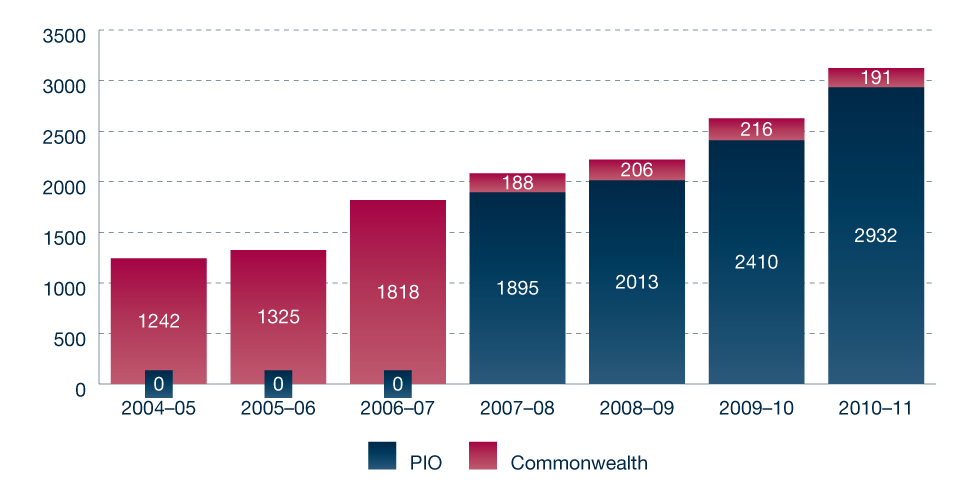

During 2010–2011 we received 305 approaches and complaints about the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE), and 32 approaches and complaints about the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPC, which was formerly the Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts – DEWHA).

This was a 30% decrease from the 494 approaches and complaints that we received about these two Departments in 2009–10. This decrease reflects the ending of a number of the Australian Government’s energy efficiency programs that were a significant source of complaints in 2009–10, particularly the Home Insulation Program and the Green Loans Program. In March 2010, responsibility for administering all energy efficiency programs transferred from the then Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (now Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities) to the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency.

Figure 5.7: Approach and complaint trends DCCEE and DEWHA 2004–5 to 2010–11

Complaint themes

The main issues that people complained to our office about concerned:

- Solar Panel Rebate decisions

- compensation arising from the Green Loans program

- the Insulation Industry Assistance Package.

Solar Panel Rebates

As we reported last year, on 9 June 2009, the Minister for the Environment announced that the Australian Government would only accept applications for the $8,000 solar panel rebate that were sent before midnight on 9 June 2009. We received many complaints about lost solar panel rebate applications. DCCEE confirmed that over 1200 applications had been reported lost. In May 2010 the Department wrote to all applicants who claimed to have submitted applications before the 9 June 2009 closure of the program, inviting them to resubmit their applications, together with supporting evidence to show that they had applied before the 9 June 2009 cut-off. Where applicants had not kept a copy of their original application, they were offered the opportunity to submit a duplicate application together with a statutory declaration to that effect. Applicants had until 4 June 2010 to resubmit their application.

Many people took up the Department’s offer and resubmitted their applications within the required timeframe. The review of these applications took some time and many applicants were not notified of the Department’s decision on their resubmitted application until November 2010. In the meantime we received many complaints about the Department’s delay in making its decision on the resubmitted applications.

In our view, DCCEE’s delay was regrettable, particularly given the short time frame that it had allowed for applications to be resubmitted and we expressed our concern to the Department.

Compensation for the Green Loans program’s cancellation

The Green Loans program was intended to assist energy efficiency initiatives in Australian homes by providing free home sustainability assessments. The assessments were voluntary and provided householders with advice on what they could do to save energy and water in their homes. However, in February 2010 as a result of well-publicised problems with the program’s delivery, the Government capped the number of home sustainability assessors at 5000, and the Department suspended issuing contracts to new assessors. In July 2010 the Government announced that the Green Loans program would be replaced by the new Green Start program. However, on 21 December 2010, the Government announced that the Green Start program would not proceed, and that the Green Loans program would continue until 28 February 2011 and then close.

The decisions to suspend issuing new contracts, and eventually to close the home sustainability assessment scheme affected thousands of home sustainability assessors who had not been able to obtain contracts with the Australian Government. Each had invested time and money on training, insurance and registration, but had never been able to obtain any work under the scheme. Those business establishment costs were essentially lost. Some assessors claimed compensation for these losses from DCCEE under the Scheme for Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA Scheme).

In recognition of the impact of its decisions on uncontracted assessors, the Government introduced a new Financial Assistance Scheme (FAS) designed to provide some compensation for uncontracted assessors. DCCEE then wrote to the assessors who had made CDDA claims and told them that it would not proceed with considering those claims, and invited them to lodge FAS claims instead.

We received a number of complaints from uncontracted assessors about the Department’s decision to discontinue their CDDA claims.

In our view, it was a positive step for the Government to introduce the FAS to provide compensation for uncontracted assessors, because FAS claims were likely to be much simpler and more straightforward to establish than CDDA claims.

As we explained to complainants, under the FAS, unlike the CDDA Scheme, claimants did not need to show either that there had been any ‘defective administration’, nor that it caused their losses. It was sufficient for claimants to show that they were an uncontracted assessor, and that they did in fact incur the kinds of business establishment costs covered by the FAS.

To establish a claim under the CDDA scheme, in contrast, claimants need to show both that there was ‘defective administration’ by an Australian Government agency, and that the defective administration directly caused their losses. In our view, in practice, both requirements were likely to be significant hurdles for uncontracted assessors. In particular, while there were undoubted failures in the governance of the Green Loans program, those kinds of governance failures did not fit easily into the CDDA Scheme’s definition of defective administration.

On the other hand, we were conscious that there might be exceptional cases where uncontracted assessors had experienced specific administrative failures, such as receiving incorrect advice from the Department, that would clearly fall within the definition of ‘defective administration’ in the CDDA Scheme. If that defective administration directly caused loss not covered by the FAS, then in our view, compensation under the CDDA Scheme should still be payable, notwithstanding the FAS.

We put this view to the Department before the FAS Guidelines were finalised, and the Department made some amendments to the Guidelines as a result. The Department explained to us that the changes were intended to ensure that the introduction of the FAS would not prevent it from considering any CDDA claims in exceptional cases.

In light of this, we invited complainants to tell us if they considered that their case was one of these exceptional ones. To date no-one has pursued their complaint with us on this basis.

Insulation Industry Assistance Package

As with the Green Loans programs, because of well-publicised problems the Government announced the closure of the Home Insulation Program in February 2010. This left insulation installers, manufacturers, importers and distributors with few prospects for their employees, and with many hundreds of thousands of dollars tied up in unwanted stock. The Insulation Industry Assistance Package (IIAP) was designed to assist these businesses by partially reimbursing them for the value of the insulation stock they were holding when the Home Insulation Program closed.