Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report 2004-05 | Chapter 7

CHAPTER 7 | promoting good administration

Introduction

A key objective of the Ombudsman's office is to contribute to public discussion on administrative law and public administration and to foster good public administration that is accountable, lawful, fair, transparent and responsive.

We pursue this objective in different ways—by looking in depth at an issue arising in a particular agency, drawing attention to problem areas across government administration, conducting own motion investigations, working jointly with agencies to devise solutions to the administrative problems that arise within government, and making submissions to external reviews and inquiries that are examining issues in public administration.

Throughout 2004–05, we made use of each of those strategies for promoting good administration within and across agencies. Another special project of the office, is work being undertaken internationally, and especially in the Asia–Pacific region, to promote good governance and administrative integrity.

Submissions, reviews and research

The Ombudsman's office is frequently invited to contribute by way of a formal submission to inquiries being conducted in Australia by parliamentary committees and executive agencies. An example discussed below is a submission to a review being undertaken by the Department of Finance and Administration (DoFA) of the Compensation for Detriment Caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) Scheme. Another submission was to a review of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation's questioning and detention powers being conducted by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service and the Defence Signals Directorate.

Review of CDDA Scheme

During the year, DoFA conducted a review of the CDDA Scheme. This review came about as a result of a report of the Australian National Audit Office, which concluded that DoFA should periodically monitor the CDDA Scheme.

The Ombudsman provided a written submission that highlighted that most complaints to the Ombudsman arose from the administration of the CDDA guidelines by different agencies, rather than from the content of the guidelines. We gave examples of complaints received about CDDA claims on matters such as:

- lack of experience of CDDA decision makers in some agencies

- rejection of CDDA claims at an inappropriate level in agencies

- reluctance by agencies to talk directly to claimants in examining claims

- a tendency to prefer an agency officer's version of events to a claimant's without proper investigation

- failure by agencies to address the core issue underlying a CDDA claim

- undue delay in deciding claims

- inadequate reasons explaining why a claim had been rejected.

One concern that we highlighted in the submission arose from instances in which compensation had been refused by an agency because of the potential availability of a court remedy. The guidelines provide that CDDA is not generally payable where a legal remedy is available to an applicant. Our concern was that a claimant should not be forced into legal action to obtain a remedy that they would not have had to pursue but for an agency's defective administration. When considering whether another remedy is available, it may be appropriate for an agency to bear in mind the principle that compensation should return the person to the position they would have been in had the defective administration not occurred.

Whistleblowing project

In November 2004, the Minister for Education, Science and Training announced that the Australian Research Council had allocated $585,000 to a research project entitled 'Whistling While They Work'.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman's office is collaborating in this three-year, national research project into the management and protection of internal witnesses (or 'whistleblowers') in the Australian public sector. The project is being led by Griffith University and involves five other universities and 12 industry partners from the Commonwealth, State and Territory public sectors.

Protecting whistleblowers and other internal witnesses to corruption, misconduct and maladministration is an ongoing challenge in public sector governance. The project will build on previous Australian and international research to assemble a more up-to-date and representative picture of how whistleblowing and related public interest disclosures are being and should be managed.

Strategies for managing internal disclosures are crucial to effective integrity systems, early detection of corruption and maladministration,and maintaining positive and healthy workplaces. They are critical to law enforcement, sound financial management, public accountability and the careers and well being of individual staff.

The Ombudsman's office is contributing significant resources to the project, including the participation of senior staff on the project steering committee, a part-time staff member to work on the project, and a one-off cash contribution of $15,000. During 2004–05, the Ombudsman and the Merit Protection Commissioner co-hosted an introductory workshop entitled 'Whistling While They Work: Enhancing the Theory and Practice of Internal Witness Management in the Australian Public Sector' attended by 45 Australian Government agency representatives. The Ombudsman also addressed a public seminar, held as part of this project, on legislative options in designing a whistleblower protection scheme.

Legislative change in migration matters

In 2003–04, we reported that the Ombudsman wrote to the Secretary of DIMIA in December 2004 recommending that action be taken to overcome the problem that certain visa holders who had successfully appealed to the Migration Review Tribunal (MRT) may still be unsuccessful in their application for a permanent visa. The specific example given was where the MRT had set aside a DIMIA decision to cancel a student visa but the student may not have been able to meet the criteria for a permanent visa if their student visa had expired before the MRT finalised its decision.

The Minister subsequently agreed to amendments to the Migration Regulations to ensure that such people would no longer be disadvantaged.

We can now report that the Migration Amendment Regulations 2004 (No. 8) 2004 No. 390 contains the appropriate amendments.

Own motion and major investigations

The Ombudsman can conduct an investigation as a result of a complaint or on his own motion (or initiative). During the year, reports were released publicly on seven own motion and major investigations. Two of the reports were completed and provided to the relevant agency in 2003–04, and were reported in last year's annual report. They dealt with the use of access powers by the ATO and the refusal by the Tax Agents' Board of NSW to provide reasons for decisions not to pursue complaints about tax agents.

The other five investigations dealt with two complaints about DIMIA concerning delay in the processing of an application for a bridging visa and a complaint about immigration detention (see 'Looking at the agencies—Immigration' section); a review of the implementation of recommendations from a review of the corporate and operational implications for the Australian Crime Commission arising from alleged criminal activity by two former secondees; and a review of the Australian Defence Force's (ADF's) Redress of Grievance system. Outlines of two of these investigations, and an outline of an investigation into administrative matters relating to the ADF's management of personnel under the age of 18 years follow. When finalised, all major investigations are reported on our website (www.ombudsman.gov.au).

Review of Redress of Grievance process

The Ombudsman has commented adversely in previous annual reports on the timeliness of the ADF's internal complaint management process, known as the Redress of Grievance (ROG) process. A project was initiated jointly in August 2004 by the Chief of the Defence Force and the Defence Force Ombudsman to conduct a wide-ranging review of the effectiveness of the ROG process. Representatives from the Department of Defence and the Commonwealth Ombudsman's office formed a Joint Review Team to conduct the review. A report was released publicly in April 2005.

It is pleasing that the Department of Defence and the ADF have since taken action to accept and to implement the recommendations in the report. This complements other action taken in recent years by the ADF to streamline the process for handling complaints submitted by its members, and to reduce the time taken to resolve complaints. Among the recommendations from the joint review being implemented were those to increase staffing levels within the department's Complaint Resolution Agency, to provide further training for investigation officers, to improve management information systems to introduce performance management and reporting standards, and to seek changes to the legislation and policies on complaint handling.

The Chief of the Defence Force noted at the time of the release of the report that he was confident ADF members would shortly notice a marked improvement in complaint handling turnaround.

Allegations of corrupt activity in the Australian Crime Commission

In June 2004, the Ombudsman conducted an own motion investigation into a review conducted by independent consultants of the operational and corporate implications for the Australian Crime Commission (ACC) of alleged corrupt activity by two former secondees. The issue was revisited by the Ombudsman in 2004–05, by examining the steps since taken by the ACC to implement the recommendations from the earlier own motion investigation. The later report concluded that the ACC had developed policies and programs to promote the concepts of professionalism and integrity as its primary corruption risk management approach.

The Ombudsman commended the ACC for its commitment to formulating a strategy to address the issues that had been identified by the independent review and the Ombudsman's own motion investigation. The Ombudsman formed the opinion that the actions taken by the ACC were appropriate and proportional responses to the issues, and indicated that further investigation of the matter was not warranted.

In his report, the Ombudsman stated that it is important for a successful anti-corruption or integrity framework that the community's trust in the integrity of policing is not misplaced. Below is an excerpt from the report released in November 2004.

It may be useful for me to make a general comment about the role of management and supervision in the ACC. A workplace culture that is actively distrustful will undermine productivity and morale. Equally, a workplace that is overly trusting can be open to manipulation and dishonesty. It is imperative that a balance is achieved in any workplace to ensure that trust is not 'misplaced'. The development of policies and practices, and the conduct of audits, can be no substitute for specialist knowledge, an awareness of roles and responsibilities, and sound judgement.

It is therefore important that managers fairly, but critically, view the actions and motivations of their staff. Failure to do so will undermine the effect of the policies that have been developed and reviewed by the ACC.

Managers should not 'suspend disbelief' when reviewing issues within their workplace. They should be able to demonstrate that they have applied intellectual rigour to understanding their responsibilities, and investigating anomalies in their workplace. Managers should also be aware of the increased likelihood of corrupt or inappropriate behaviour occurring in the workplace when trust is misplaced.

Young people in the military

During 2004–05, Ombudsman staff completed an own motion investigation into administrative matters relating to ADF's management of personnel under the age of 18 years. The investigation was in response to several serious complaints made to the office about the adequacy of Defence's administration of its younger personnel.

The investigation looked at the ADF's policies and procedures for dealing with young people; at the mechanisms in place to ensure that staff understand their obligations to young people and that policies are implemented; and at how complaints from young people are handled by the ADF.

A draft report on the investigation was provided to the Chief of the Defence Force in June 2005 for comment. A final report on the investigation is expected to be released late in 2005, and will be reported in the Ombudsman's 2005–06 annual report.

International cooperation and regional support

The Ombudsman institution is now found in countries around the world. Offices established in over 130 countries are members of the International Ombudsman Institute (IOI), of which the Commonwealth Ombudsman's office is a member. The Asia–Pacific Ombudsman Region (APOR) is a vibrant branch of the IOI. Our office is playing an active role regionally and in this global network to promote principles of administrative justice and good governance.

The office's international program expanded considerably during 2004–05, with the support of funding from the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID). The office has worked closely with other Australian Ombudsman offices to establish a program of mutual cooperation and assistance with Ombudsman offices in Asia and the Pacific.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman attended the IOI Conference, which is held every four years, in Quebec City, Canada in September 2004. In the years between IOI Conferences, an annual conference of APOR members is held. This year it was held in Wellington, New Zealand in February 2005. Conference attendees in Wellington studied the problems of small offices, with the Commonwealth Ombudsman giving a paper on institutional strengthening in this context.

A senior representative from our office attended a Human Rights and Complaint Handling Conference in Malawi in February 2005 to provide information and training sessions on Australian administrative law, the operations of the Commonwealth Ombudsman's office, and alternative dispute resolution. The Danish Institute of Human Rights supported this visit on behalf of the Malawian Body of Case Handling Institutions.

In 2004–05, funding from various AusAID programs supported our office's international activities to facilitate the exchange of specialist advice, training, technical assistance and support to the National Ombudsman Commission of Indonesia, the Thailand Ombudsman, and the Ombudsmen in the Cook Islands, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu.

Indonesia

We have been working with the National Ombudsman Commission of Indonesia over several years. Early activities included training in Australia specifically about the roles, values and competencies required of ombudsman staff.

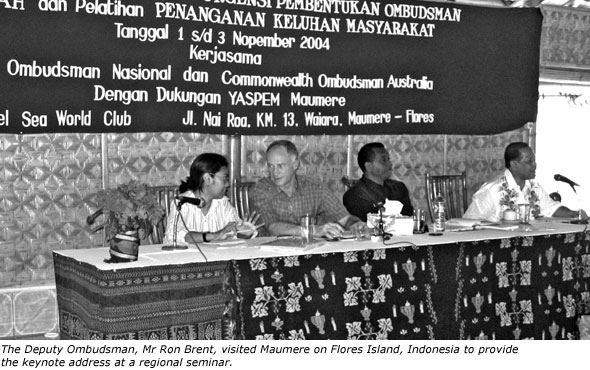

The present situation in Indonesia is one of rapid change and numerous challenges. The commission is working to establish regional ombudsman offices and perceives that decentralising services is an important change from a top-down system of government to a more open system. The commission has translated training material—received during its participation in the 2003–04 Commonwealth Ombudsman Advanced Investigation Course—into Indonesian and is presenting it regionally through a seminar process. This seeding process has established some regional ombudsman services and stimulated regional demand. During 2004–05, we supported five of these seminars, directly participating in two.

Our Information Technology Director visited Jakarta in May 2005 to provide advice on the information technology framework and business planning needs to be considered for the commission's central and decentralised offices. This resulted in a Strategic Information Technology Plan, which we will continue to support where possible through providing strategic advice.

Thailand

During 2004–05, training has been the predominant activity with the Thai Ombudsman's office. The director of our Law Enforcement Team visited Thailand in April 2005 to look at maximising returns from training in Australia through transfer processes that would build training capacities within the Thai office.

We sponsored four senior investigation officers to attend training courses in Australia: a four-week ANU Ombudsman Professional Short Course in October 2004; and the Police Integrity Investigation Course run jointly by the Australian Federal Police and the Commonwealth Ombudsman in June 2005.

Papua New Guinea

We are developing a close working relationship with the Ombudsman Commission of Papua New Guinea through staff placements and other activities. Our aim is to establish an ongoing twinning relationship to gradually raise skill and knowledge levels. One of our staff members completed a three-month placement in Port Moresby in June 2005, developing initial relationships and an outline of a three-year strategic twinning arrangement. A second placement will commence in August 2005.

Pacific island regional strengthening

We have taken a coordinating role in working to strengthen regional sharing of skills and knowledge amongst ombudsmen in the Pacific island region. The Ombudsman of Fiji is taking on the role as lead counterpart agency for the Pacific nations of the Cook Islands, Fiji, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman and New South Wales Ombudsman co-hosted a Forum of Pacific Island Ombudsmen prior to the APOR Conference in Wellington in February 2005 to present the recommendations from a scoping study. This provided a strong base for further discussion, an opportunity to address immediate concerns, and the basis for a proposal to AusAID for a medium-term project to commence in 2005–06.

Activities and progress to date include implementing a professional peer network; initiating a three-month trial to provide a legal/strategic resource for south-west Pacific Ombudsmen; supporting sessions on strategic and business planning; organising two staff to work in the Fijian and Samoan Ombudsmen's offices for three weeks; and facilitating training for a senior investigation officer from each of the Ombudsman offices in the Cook Islands, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu.

Other international cooperation

Another means of international cooperation has been to host senior-level delegations from several foreign offices, including from the Republic of Maldives, China, the United Kingdom, Korea and Indonesia.

Cooperation among Australian Ombudsmen

There are a large number of ombudsman offices established in Australia, in the public and private sector. Internationally, Australia has one of the most developed frameworks of ombudsman offices.

There is a close cooperation among Australian ombudsman offices, both informally and formally. At the formal level, there are two groupings in which the Commonwealth Ombudsman is an active participant. One is the APOR of the International Ombudsman Institute. Membership of the APOR comprises the public sector ombudsman offices established in this region. A major project of the members of APOR has been the development of the regional cooperation program described earlier in this chapter.

The other grouping is a new association formed in 2003, the Australian and New Zealand Ombudsman Association (ANZOA). The association was established by industry ombudsman offices in Australia, but membership is open generally to any ombudsman office. The Commonwealth Ombudsman is a member of the Executive of ANZOA. Projects on which ANZOA has been active over the past year include identifying and addressing systemic issues, training and accreditation of staff, benchmarking of complaint workloads and efficiency, the review of ombudsman schemes, and internal review of complaint handling within ombudsman offices.

In June 2005, the first meeting of its kind attended by most public sector and industry Ombudsmen in Australia and New Zealand was held in Canberra, hosted by the Commonwealth Ombudsman. The meeting of seventeen Ombudsmen was attended by Australian State Ombudsmen (from New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia); Australian industry Ombudsmen (Banking and Financial Services Ombudsman; Financial Industry Complaints Service; Energy and Water Ombudsmen from NSW and Victoria; General Insurance Ombudsman, and Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman); and from New Zealand, the Chief Ombudsman, Banking Ombudsman, Electricity Complaints Commissioner, and Insurance and Savings Ombudsman.